By: Dave Vance

DNA testing opens new doors—but that first match list can be overwhelming. This guide walks you through your Family Finder™ DNA results, step-by-step.

If you just received your Family Finder DNA results and don’t know what to do next, you’re not alone. Your DNA match list can look like a jumble of names, numbers, and acronyms—but with the right tools and a little strategy, it can become one of the most powerful resources in your family history journey. This guide will help you learn how to understand your Family Finder DNA matches and start making meaningful genealogical connections—without needing a genetics degree.

Welcome to a New Dimension of Family History!

How many hours have you spent poring over census records, wills, and old photographs, piecing together your family genealogy? Many people hope that DNA testing will shorten their genealogy journey, and it certainly can… but it can also be frustrating when you get your first list of DNA matches and it’s not clear how any of them are related to you.

It’s natural to be worried that you need to learn all about genetics and genetic testing to understand what to do next; and if you’re interested in those topics certainly you can learn more about them, but that’s not how you make progress with your genealogy.

What Your Family Finder DNA Test Can (and Can’t) Tell You

Your Family Finder autosomal DNA test examines the DNA inherited from all your recent ancestral lines. Think of it as a unique inheritance from each of your ancestors over the past five to seven generations. This makes it incredibly useful for:

- identifying living relatives (cousins of various degrees.)

- confirming suspected relationships in your tree.

- potentially breaking through “brick walls” where the paper trail has gone cold.

While the ethnicity percentages provided are interesting, the core genealogical value lies in your list of DNA matches – other individuals who share identifiable segments of DNA with you.

Any introduction to autosomal DNA will tell you that it is reshuffled with each generation (a process called recombination). This means that while it’s excellent for connecting with relatives who share ancestors with you within about a 5-7 generation window, its ability to pinpoint very distant specific ancestors through DNA matches alone diminishes.

A match predicted as a “4th to 6th cousin” won’t typically come with a label identifying your exact common great-great-grandparent; that discovery still requires the diligent genealogical research you’re accustomed to, now guided by these genetic clues. Autosomal DNA provides probabilities and signposts, not instant answers for more distant connections. Understanding this from the outset helps align expectations with the exciting, but often methodical, process of DNA-assisted research.

Setting Expectations

It’s also important to realize that you don’t have to make sense of every match. Some of those other testers may know their ancestry much further back than you do; some of them may know nothing about their ancestry at all. So for some matches it may be obvious where your common ancestry is, and with other matches you may never be able to figure out those connections. That’s perfectly normal.

Your main objective doesn’t really need to be understanding the entire list of matches; you can often make more progress either by:

- working first with your closest matches and moving out from there to more distant ones

or

- first identifying those matches who are more likely to help you answer your most important questions.

Setting these realistic expectations allows you to more effectively integrate DNA evidence into your existing research. Finding just one 3rd cousin match that can help you with a particular brick wall or family mystery can make it all worthwhile, but that match probably won’t jump off the page at you; you just need to work through all this new information to find those matches.

A Word About Tools

While you’re focusing on your autosomal (Family Finder) results, it’s worth noting FamilyTreeDNA also offers Y-DNA (for the direct paternal line) and mitochondrial DNA (for the direct maternal line) tests, which are invaluable for deep ancestral research along specific lines.

For autosomal analysis, FamilyTreeDNA provides a robust set of tools like:

- The Chromosome Browser, which allows you to see the specific segments of DNA shared with matches (a powerful tool for confirming relationships)

- Advanced Matches, matrix reports showing you levels of connections between groups of matches

- The well-regarded Group Projects system (where you can join surname, geographical, or haplogroup projects to collaborate)

Familiarity with these tools can enhance your research strategy.

Navigating Your FamilyTreeDNA Results: A First Look

With your Family Finder results in hand, it’s time to explore your dashboard.

Logging In and Locating Your Matches (myOrigins, ancientOrigins, and Family Finder Matches)

After logging into your FamilyTreeDNA account, you’ll typically be on your main dashboard. Look for a section or link related to “Family Finder” or “Autosomal DNA.” This will lead you to your results, which usually include:

- myOrigins: An estimate of your ethnic makeup, showing percentages from various global regions.

- ancientOrigins: A comparison of your DNA to DNA from ancient archaeological sites.

- Family Finder Matches: Your list of other individuals in the FamilyTreeDNA database who share significant DNA with you.

While myOrigins and ancientOrigins offer broad historical context, your Family Finder Matches list is the key to connecting with living relatives and extending your known family tree.

Understanding the Key Measurements: Centimorgans (cM) and Shared Segments

Your Family Finder Matches list will display names (or kit numbers/aliases) alongside numbers indicating the amount of shared DNA. The two most important figures are centimorgans (cM) and shared segments.

A centimorgan (cM) is the unit of measurement for shared DNA. Simply put, the more cM you share with a match, the closer the likely genealogical relationship. For example, parents and children share approximately 3400 cM, while more distant cousins share progressively smaller amounts.

Shared segments refer to the number of blocks of DNA you share. Generally, more segments, and particularly longer segments can also indicate closer relationships, though the total shared cM is the primary initial guide. (FamilyTreeDNA also reports the “longest block.”)

It’s crucial to remember that cM values for specific relationships fall within ranges due to the random nature of DNA inheritance. A small amount of shared DNA (e.g., 15 cM across several tiny segments) might sometimes represent very distant, population-level sharing rather than a traceable recent common ancestor.

Misinterpreting a cM value as a definitive relationship without considering the possible range can lead to misdirected research. Understanding that 100 cM, for instance, could represent several potential relationships (e.g., first cousin once removed, second cousin) is key.

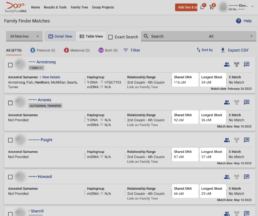

To help you correlate cM values with potential relationships, the following table offers a general guide, based on data like that from The Shared cM Project.

Note: These are approximate ranges. The Shared cM Project offers more detailed probabilities.

This table helps translate raw cM numbers into potential relationship terms, guiding your initial assessment and helping you prioritize which matches to investigate first.

A Valuable Resource: “DNA Explained”

Throughout your genetic genealogy journey, reliable expert resources are invaluable. The blog dna-explained.com, by Roberta Estes, is highly recommended for its thorough, data-driven, yet accessible articles on all aspects of genetic genealogy. It’s a worthwhile site to bookmark.

The dnaeXplained blog features detailed case studies illustrating how DNA, combined with traditional research, solves family mysteries. It also provides tutorials for FamilyTreeDNA tools and clear explanations of complex topics.

Analyzing Your Match List: Initial Strategies

Once you’ve had a chance to absorb the basics of how autosomal DNA works, it’s time to roll up your sleeves and start working through your match list. This part can feel overwhelming—there might be hundreds or even thousands of names staring back at you. But don’t panic! With a few simple strategies, you can quickly start to identify which matches are worth your time and how to prioritize them in your research. This section will walk you through those first crucial steps.

Sorting and Filtering: Organizing Your Genetic Clues

FamilyTreeDNA typically sorts your match list by total shared cM, highest first. This is ideal, as higher cM generally indicates a closer relationship. However, you can also sort by other criteria, such as match name or longest shared DNA block.

Filtering tools are essential for managing potentially long match lists. You can filter by:

- matches who list a particular ancestral surname you’re researching

- an ancestral location relevant to your work

- X-chromosome matches

- “In Common With” another selected match (which we’ll cover in a minute)

Starting with your closest matches (those who share larger amounts of cM with you) is often a good strategy; partly because these are more likely to be closer relatives and it is easier to identify your closer common ancestors.

Many people have few close matches but many many more distant ones, so often starting genetic genealogists may be told to not look at matches below thresholds like 20 cM. This topic gets us into more complicated areas like the effects of endogamy and identical-by-chance matches; fascinating areas in their own right but not necessary ones for those just getting started. So if you can, stick first with matches who share the largest amounts of cM with you.

Many genealogists new to DNA may not initially leverage the full power of these tools. Learning to sort by shared cM and then apply filters (for example, to show only matches sharing over 20 or 40 cM who also have a public family tree) makes the list far more manageable and your efforts more targeted.

Identifying Your Closest Matches: Your Starting Point

- Begin by examining your top matches (highest shared cM).

- Click on their profile to see the shared cM, number of segments, and longest block.

- Look for known close relatives first (parents, siblings, first cousins if they’ve tested). Confirming these helps you get oriented.

- Then, move to the next tier of high-cM matches.

While a more distant match sharing a key surname from one of your brick wall lines might be tempting to investigate immediately, it’s generally more effective to first identify and, if possible, figure out the connections with your closest genetic relatives. These connections provide crucial anchor points and known ancestral lines, which then serve as a foundation for tackling more distant or complex matches.

Successfully placing even a few close matches can be very validating, confirming branches of your tree and providing a practical understanding of how DNA inheritance works in your own family.

The Indispensable Family Tree (Yours and Theirs!)

As you know, DNA results yield their greatest insights when combined with traditional genealogical research. It’s essential to have your own family tree, as comprehensively documented as possible, linked to your DNA results in your FamilyTreeDNA profile. For this, FamilyTreeDNA has partnered with MyHeritage so you can use their family tree building tools but still link individuals in the MyHeritage family tree back to your FamilyTreeDNA matches.

When examining DNA matches, check if they have a linked family tree. If available, explore it for common surnames, ancestral locations, or specific individuals that overlap with your known ancestry. Not all matches will have a tree, and some may be private.

The presence of well-researched trees for both you and your matches is often a primary determinant of success. If two individuals share significant DNA and both have well-documented public trees, finding the common ancestral couple can be relatively straightforward. Conversely, the absence of trees makes the process significantly more challenging.

Building and attaching your own tree not only aids your research but also makes you a more valuable match for others, fostering the collaborative ecosystem that is central to genetic genealogy. As we’ve said before, “genealogy is a team sport.”

What Should You Do With Your Matches As You Identify Them?

As you identify matches and find their connections and your shared ancestors, it helps to add those matches and their connections to your family tree. This allows you to link the match in FamilyTreeDNA back to their place in your MyHeritage Tree, and also makes that information immediately available to you when you find other matches who share DNA with you and that match.

Some researchers go further and work to identify the common ancestors who can be associated with specific segments of their DNA. While this can also be a powerful tool to quickly identify your connection with future matches, it’s better to leave this approach at first and just concentrate on identifying your connections to as many matches as possible.

The information you collect from that first analysis will help you more easily do “segment mapping” (as it’s often called) at a later stage if you decide to.

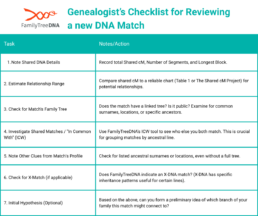

To help organize your initial review of a new match, consider this checklist:

This checklist provides a methodical approach to evaluating each significant match, ensuring you gather key information for analysis.

Next-Level DNA Match Strategies

Now that you’ve reviewed your match list and started identifying your closest genetic relatives, you may be wondering how to go further. This section introduces a few key tools within FamilyTreeDNA that can help you begin grouping matches and understanding how different relatives may connect. These approaches don’t require advanced genetics—just a bit of curiosity, pattern recognition, and a willingness to follow the clues your DNA provides.

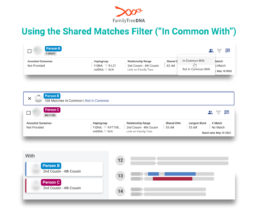

Understanding Shared Matches (In Common With – ICW)

The “In Common With” (ICW) feature (or “Shared Matches”) is one of your most powerful tools. If you (A) match Person B, and you (A) also match Person C, the ICW tool on Person B will show you all of your other matches who also match Person B.

If you (A), Person B, and Person C all match each other on the same segment of DNA, they form what’s called a triangulated cluster, likely sharing a common ancestor or ancestral couple. This is invaluable for sorting matches.

For example, if you have a known maternal first cousin (Cousin Mary) in your match list, using the ICW filter on her will show you other matches likely related through your shared maternal line. This instantly helps assign a group of matches to a specific family branch.

Roberta Estes’ blog, dnaeXplained, is a great resource with many examples that consistently emphasize using triangulated groups for grouping matches and identifying common ancestral lines, often showcasing its role in solving complex cases.

The ICW filter transforms an undifferentiated list of matches into interconnected clusters, which is the first step towards identifying common ancestors for groups of matches, rather than tackling each one in isolation.

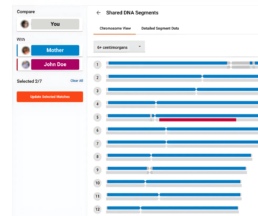

The Chromosome Browser: Visualizing Shared DNA (A Genealogist’s Perspective)

FamilyTreeDNA’s Chromosome Browser allows you to see where on your 22 pairs of autosomes you share specific DNA segments with your matches. While it may appear technical, its basic utility is straightforward and genealogically valuable. The chromosome browser is also essential for triangulation.

A primary use for genealogists is to help determine:

- If a match is on your paternal or maternal side, if you’ve also tested one or both parents

- If another close relative whose exact relationship is known (e.g., a full sibling, an aunt/uncle whose line is confirmed)

If you and your mother both match “John Doe” on the exact same segment on Chromosome 5, John Doe is almost certainly related through your maternal line.

Triangulation: Confirming Ancestral Lines (Simplified)

Triangulation is a more advanced concept, but in its simplest form, it involves you (Person A) and two DNA matches (Person B and Person C). (Three points, like a triangle.) Triangulation occurs when:

- Person A matches Person B on a specific DNA segment.

- Person A also matches Person C on that exact same DNA segment.

- Crucially, Person B also matches Person C on that exact same DNA segment (this third “leg” must be verified).

If all three conditions are met, it’s highly probable all three inherited that segment from a common ancestor or ancestral couple. Triangulation is a robust method for confirming that a specific DNA segment, and thus the relationship it implies, descends from a particular ancestral line.

For now, focus on ICW and basic chromosome browser use. However, understanding the principle of triangulation is valuable. Awareness of triangulation helps you appreciate the rigorous standards of proof possible in genetic genealogy, moving beyond simple cM comparisons to more precise methods of verifying ancestral connections.

Making Contact: Reaching Out to Your DNA Relatives

So you have identified promising matches but they don’t have family trees or you can’t figure out your common ancestors? It may help to simply ask them. Communication can lead to sharing invaluable family tree information, photographs, stories, and ultimately, identifying your common ancestors.

Crafting an Effective First Message to a Fellow Genealogist

Your initial message to your DNA matches can significantly impact the response. A clear, concise, polite, and genealogically informative message is best.

Key elements include:

- Keep it brief and friendly.

- Identify yourself clearly: State your name (or kit name) and mention you’re a DNA match at FamilyTreeDNA.

- Quantify the connection: Mention total shared cM (e.g., “We share 120 cM of DNA…”).

- State your specific research interest: “I am researching my paternal grandmother’s Harrison line from County Cork, Ireland, particularly focusing on descendants of John Harrison (b. c1820), and noticed we are a DNA match. I am hoping to discover how our families connect.”

- Mention your family tree: If you have an online tree, mention it and offer to share a link. This shows you’re an active researcher.

- Ask a targeted genealogical question (if appropriate): “Do you have any ancestors with the surname ‘O’Malley’ from the parish of Annaghdown, Galway, in your family tree?” Or, “I see from your profile you list ‘Schmidt’ as an ancestral surname; my Schmidt ancestors were from the Baden region of Germany in the early 1800s. Does this resonate with your research?”

- Thank them for their time.

A well-crafted message, tailored with your specific genealogical queries, demonstrates respect for the match’s time and establishes you as a knowledgeable researcher, increasing the likelihood of a productive exchange.

What Genealogical Information to Share (or Initially Hold Back)

It is ideal to share basic ancestral surnames, locations, and timeframes relevant to the potential connection. If you have a hypothesis (e.g., “Our shared DNA, along with the fact we both have ancestors named Smith from Anytown, Virginia, in the mid-1800s, suggests a connection through that line”), mention it briefly.

Avoid overwhelming the match with your entire database or numerous complex questions in the first message. The goal is to open a dialogue. Always be mindful of privacy for living individuals.

Sharing specific, relevant genealogical details also increases the chance the match can quickly identify a point of overlap with their own research.

Managing Expectations and Responses from Matches

Not everyone who tests their DNA is actively engaged in research or responsive. Some test out of curiosity, others have limited time. Responses can take days, weeks, or months. Patience is key.

Be prepared for varying levels of genealogical knowledge from your matches. Some will have extensive, documented trees; others may have little information. Understanding that response rates vary helps prevent discouragement and allows you to value the collaborations that do develop.

Building on Your Discoveries: Integrating DNA into Your Research

Identifying and contacting matches is just the beginning. The real work lies in integrating these genetic clues with your traditional research.

Integrating DNA Evidence with Traditional Genealogy: A Powerful Synergy

DNA evidence is a powerful clue, best used in conjunction with documentary evidence. Since our ancestors’ names are obviously not written in our DNA, breakthroughs usually occur where DNA findings are corroborated by records. If DNA suggests a cluster of matches descends from a specific ancestral couple, your next step is to find traditional records (census, vital records, wills, land records) that support this and trace the lines of descent.

DNA can point you to where to look for records. If matches have ancestors in a county previously unknown to you, that’s a strong lead. Conversely, DNA can help confirm or refute hypotheses based on a paper trail. Again you can find many examples of this on dnaeXplained where DNA provided the crucial hint to break a documentary brick wall, or led to the right documents which provided the context for a genetic connection.

This integrated approach, where genetic and traditional evidence cross-validate each other, leads to more robust genealogical conclusions.

Common Pitfalls for Genealogists New to DNA

While your genealogical skills are a great asset, here are some DNA-specific pitfalls:

- Over-reliance on ethnicity estimates for specific connections: Use the match list for genealogical matching.

- Ignoring matches with no trees: They might still be part of a key ICW cluster or respond with information.

- Confirmation bias: Be open to DNA evidence that contradicts a long-held theory.

- Not building out their own tree sufficiently with DNA in mind: Ensure your tree is robust enough to identify common ancestors with matches who may be several generations removed.

- Poor record-keeping of DNA match details: Develop a system to track matches, shared cM, communications, and hypotheses.

- Giving up too easily on a DNA puzzle: New matches test daily, and new insights can emerge over time.

Working through your DNA match list may seem overwhelming at first, but by starting with your closest matches and using the available tools, you’ll quickly gain clarity and confidence. The strategies in this guide are designed to help you learn how to understand your Family Finder DNA matches and apply that knowledge to your ongoing family history research.

If you’ve used these approaches to identify a new relative, confirm a theory, or break through a brick wall, we’d love to hear your story. Sharing what you’ve found could help another researcher take their next step forward.

About the Author

Dave Vance

Senior Vice President and General Manager for FamilyTreeDNA

Dave Vance is a life-long genealogist with a professional career in IT services. He took a National Genographic Project DNA test in 2005 and has been a genetic genealogy enthusiast ever since to the mild consternation of his family and friends. He has been the editor of the Journal of Genetic Genealogy, is a surname Group Project Administrator and haplogroup Group Project Co-Administrator, has written tools, books, and articles on genetic genealogy, and finds occasions to speak publicly about various genetic genealogy topics even when he wasn’t invited to do so beforehand.