Genes and Screams is a seasonal series linking genetic genealogy with history’s spookiest figures. Discover how DNA sheds light on mummies, vampires, and witches across time. You can read the rest of the series here:

By: Courtney Eberhard

From Egypt to the Americas, explore eerie DNA connections to mummies you may share in your family tree this Halloween season.

Welcome to spooky season; a time for some to prepare for Halloween, and others (like me) to use Halloween as an excuse to fill blog posts with spooky humor and science. This season, I will highlight a different Halloween creature, tying them to our real-world database, research, and discoveries.

And since Brendan Fraser is making a well-deserved comeback (yes, that star of The Mummy), it feels like the perfect time to dig into the real mummies of history and see how modern DNA testing reveals genetic links between ancient remains and living descendants today.

During one of my late-night scrolls, my feed was already full of Halloween posts. You know the ones—year-round spooky friends who start planning costumes before the pumpkins even hit the shelves. They post about skeletons, witches, monsters… and yes, mummies.

The mummy costume is a classic. Cheap, iconic, and surprisingly close to reality. With just a roll of toilet paper, a lot of tape, and total acceptance that your costume will disintegrate in seconds, you’re essentially reenacting an ancient preservation ritual (except with low quality textiles). Because mummies aren’t just movie monsters. They’re real, and their DNA still speaks through modern science.

Can You Be Related to a Real Mummy?

Short answer? Yes! If you’ve tested your DNA, you might share a haplogroup with an actual mummy.

It sounds like the setup for a Halloween joke, but the science is real. Mummies are preserved human remains, and thanks to advances in ancient DNA analysis, researchers can extract and sequence the genetic material that’s survived for thousands of years. By comparing that data to the global Y-DNA and mtDNA databases (like ours at FamilyTreeDNA), scientists can trace direct paternal and maternal lineages that connect living testers to ancient individuals.

So, when you browse your Discover™ haplogroup reports and see a match to a historical haplogroup—like those belonging to King Tut, Ramesses III, or even the Spirit Cave Mummy—you’re not just looking at names in a database. You’re peeking into a 9,000-year-old family tree where you and a real mummy share a distant ancestor.

Do Mummies Have DNA?

Absolutely. While time, climate, and burial conditions can damage genetic material, fragments often remain preserved in bones, teeth, and soft tissue. These fragments allow scientists to reconstruct partial or full genomes—unwrapping ancient ancestry and migration patterns once thought lost to time.

In short: mummies can’t come back to life (sorry, Hollywood), but their DNA can revive their legacies.

What Have DNA Tests Revealed About Mummies?

So, now that we’ve established that mummies have DNA (and that you might even share some of it), let’s unwrap what DNA testing has actually revealed about these ancient individuals. From the tombs of Egypt to the caves of the Americas, haplogroup analysis has turned centuries-old mysteries into traceable genetic connections.

Each discovery tells a different story. Some about royal bloodlines, others about the earliest ancestors of modern populations. Either way, the past isn’t as distant as it seems when its DNA is still found in living testers today.

DNA Links Between Ancient Egypt and Modern Testers

Few civilizations capture the imagination like ancient Egypt, where monuments, mummies, and mysteries have endured for thousands of years. But beyond the golden tombs and hieroglyphs, DNA analysis is revealing the genetic legacies of Egypt’s pharaohs and nobles, tracing how their paternal and maternal lines connect to people living today.

Thanks to advances in Y-DNA and mtDNA sequencing, researchers can now read the genetic signatures preserved within these royal remains—offering insight into dynastic relationships, population migrations, and the complex heritage of one of the world’s earliest civilizations.

The following mummies represent some of the most studied individuals in history, their genomes serving as time capsules of ancestry that bridge the ancient Nile to the modern world.

King Tut, Yuya, and Thuya — Royal Roots Written in DNA

Long before the discovery of King Tutankhamun’s glittering tomb in 1922, his story began generations earlier—with Yuya and Thuya, two of ancient Egypt’s most influential nobles. Their descendants would define the 18th Dynasty, shaping one of history’s most storied royal bloodlines.

Yuya and Thuya: The Power Couple of the 18th Dynasty

Yuya and his wife Thuya lived during Egypt’s 18th Dynasty, a period of wealth, artistry, and religious transformation. Yuya, from the city of Akhmin, served as a trusted adviser to Pharaoh Amenhotep III, holding prestigious titles such as King’s Lieutenant, Master of the Horse, and Father-of-the-God—a title reflecting his role as Amenhotep’s father-in-law. In Akhmin, Yuya also served as Prophet of Min, the local fertility god, and Superintendent of Cattle, overseeing the herds dedicated to temple offerings.

Thuya, believed to be a descendant of Queen Ahmose-Nefertari, held positions of remarkable influence in Egypt’s interconnected religious and governmental life. She was a Singer of Hathor, Chief of the Entertainers of both Amun and Min, and Superintendent of the Harem of these gods. She likely died around 1375 BCE, in her early to mid-50s, having lived a life of devotion, authority, and prestige rarely matched by women of her era.

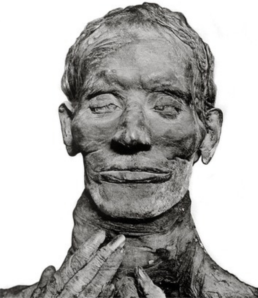

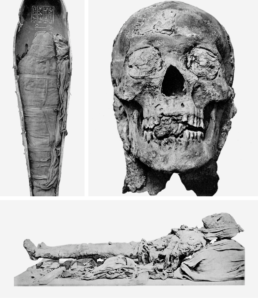

When their tomb was discovered in the Valley of the Kings in 1905, archaeologists were stunned. Though robbed in antiquity, the burial remained one of the most spectacular ever found before Tutankhamun’s discovery. Their mummies were extraordinarily well preserved, their faces almost lifelike—offering an unprecedented glimpse of what two powerful Egyptians from the 14th century BCE truly looked like.

Genetic testing has identified Yuya’s Y-DNA haplogroup as G-P15 and both Yuya and Thuya’s mtDNA haplogroup as K, a lineage found widely across North Africa, the Near East, and the Mediterranean. Their DNA provides a tangible link between Egypt’s elite and the broader population movements of the ancient world.

King Tutankhamun: The Descendant Who Became a Legend

Their great-grandson, Tutankhamun, ascended the throne around 1332 BCE during a time of religious upheaval. Born Tutankhaten, he inherited the aftermath of his father Akhenaten’s monotheistic revolution—the brief and controversial worship of the Aten. As pharaoh, Tutankhamun restored Egypt’s traditional polytheistic religion, reestablished the cult of Amun at Thebes, and moved the royal court from Amarna back to Memphis. His reign, though short, became one of the greatest restoration periods in Egyptian history, celebrated on the Restoration Stela.

Tutankhamun renewed diplomatic relations abroad, led military campaigns, and was one of the few pharaohs to be worshiped as a deity during his lifetime. Although his tomb and mortuary temple were unfinished at the time of his death at nineteen, what remained was extraordinary.

When Howard Carter and his team discovered his nearly intact tomb in 1922, it became a global sensation. Inside lay more than 5,000 artifacts—including the pharaoh’s world-famous golden mask—and the remarkably preserved mummy of the boy-king himself. While tales of a “pharaoh’s curse” captured the world’s imagination, modern science captured something far more enduring: his DNA.

Analysis revealed that Tutankhamun inherited his paternal Y-DNA haplogroup R-M343 and his maternal mtDNA haplogroup K—the same maternal line as his great-grandmother Thuya. These results confirm the close familial relationships within Egypt’s royal house and reveal the genetic continuity that defined the 18th Dynasty.

Today, with the updated Y-DNA and mtDNA Trees of Humankind, these royal lineages can be explored in FamilyTreeDNA’s Discover Haplogroup Reports. Yuya and Tutankhamun appear in the Y-DNA Reports, while Yuya, Thuya, and Tutankhamun are featured in the mtDNA Reports—allowing modern testers to see how their own paternal and maternal lines connect to Egypt’s most renowned dynasty.

Ramesses III — Haplogroup E-P2: Shadows of a Pharaoh’s DNA

If your Y-DNA belongs to haplogroup E-P2, your paternal line traces back to the royal courts of Usermaatre Meryamun Ramesses III, the second pharaoh of Egypt’s Twentieth Dynasty. Born around 1217 BCE, Ramesses III ruled for 32 years (c. 1186–1155 BCE) and is remembered as the last pharaoh of the New Kingdom to wield substantial power.

A son of Setnakhte and Tiy-Merenese, Ramesses III secured his throne during a time of political unrest and restored stability through military campaigns and monumental works like Medinet Habu, his mortuary temple at Thebes. But even at the height of his reign, turmoil brewed inside the palace walls.

In 1155 BCE, one of his wives, Queen Tiye, conspired to place her son Pentawer on the throne instead of the chosen heir Ramesses Amenherkhepshef (later Ramesses IV). The infamous Harem Conspiracy, preserved in ancient trial papyri, ended in tragedy. Forensic study of both mummies later confirmed their familial link and revealed violent deaths—Ramesses III’s throat was cut, and his son’s burial suggests a forced, dishonored end.

Modern DNA testing has placed Ramesses III within haplogroup E-P2, a major Y-chromosome lineage that today appears widely across Africa and the Near East. His result was part of a broader reclassification of the E haplogroup following new research by FamilyTreeDNA scientists.

More than 3,000 years later, the same Y-DNA branch that once ruled Egypt endures in living men around the world—a reminder that even in tales of betrayal and dynasty, family still connects us through DNA.

The Tomb of the Two Brothers — Haplogroups H-Z19008 (Y-DNA) and M1a1 (mtDNA): Ancestry Entombed

in DNA

Nestled in Deir Rifeh, Egypt, the Tomb of the Two Brothers offers one of the most fascinating glimpses into the 12th Dynasty of the Middle Kingdom (c. 1985–1795 BCE). Discovered in 1907 by workmen under Flinders Petrie and Ernest Mackay, the chamber held two high-status priests—Nakht-Ankh and Khnum-Nakht—whose ornate coffins and burial goods now reside in the Manchester Museum.

The small chamber sat within the courtyard of a larger governor’s tomb, suggesting the pair’s noble connections. Each man was buried in a nested set of wooden coffins, intricately decorated with palace-façade motifs and hieroglyphic inscriptions naming their mother, Khnum-aa. Titles on their coffins identify Nakht-Ankh as “Son of a Governor” and Khnum-Nakht as “Wab-Priest of Khnum, Lord of Shashotep.”

When the mummies were unwrapped in 1908, differences in their skeletal features led some scholars to doubt their brotherhood. More than a century later, ancient DNA sequencing finally settled the question. In 2018, researchers from the University of Manchester extracted DNA from the brothers’ teeth and sequenced both their mitochondrial and Y-chromosome fragments. The study revealed that both men shared the mtDNA haplogroup M1a1, confirming a common mother—but their Y-chromosome sequences differed, indicating that they had different fathers.

That same paper placed Nakht-Ankh’s Y-DNA within haplogroup H-Z19008, refining our understanding of his paternal lineage. Together, these findings from the University of Manchester represent the first successful typing of both mitochondrial and Y-chromosomal DNA in Egyptian mummies—a groundbreaking moment in the study of kinship and identity in the ancient world.

Morphological analysis further highlighted their individuality: Nakht-Ankh displayed features typical of northern Mediterranean ancestry, while Khnum-Nakht exhibited traits more common in African populations—underscoring Egypt’s long-recognized diversity during the Middle Kingdom.

Today, Nakht-Ankh’s paternal lineage (H-Z19008) and both brothers’ maternal lineage (M1a1) appear in FamilyTreeDNA’s Discover Reports, inviting modern testers to explore how their own DNA might trace back to these extraordinary men whose family story was literally written into the walls of their tomb—and preserved in their genes.

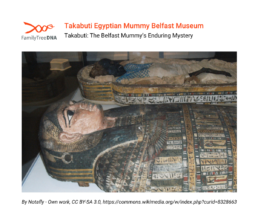

Takabuti — Haplogroup H4a1 (mtDNA): The Belfast Mummy’s Enduring Mystery

In 1834, a beautifully wrapped Egyptian mummy arrived in Belfast, Northern Ireland, captivating local audiences and scholars alike. The following year, she became one of the first mummified individuals ever unwrapped on the island of Ireland, revealing the face of a woman who had lived more than 2,600 years earlier. Her name, Takabuti, was identified through hieroglyphs on her coffin—an ordinary woman whose story would become anything but.

Takabuti lived around 660 BCE, during Egypt’s 25th Dynasty, a period marked by political transition and Nubian influence. She was a married woman of high status, likely the mistress of a great house in Thebes, as indicated by inscriptions on her coffin. Her carefully preserved remains eventually became one of the Ulster Museum’s most iconic residents, studied for nearly two centuries.

Modern research has transformed what we know about her. Between 2006 and 2020, a collaborative project led by National Museums NI, Queen’s University Belfast, and the University of Manchester’s KNH Centre for Biomedical Egyptology launched a multi-phase study known as The Takabuti Project. Their findings culminated in the book The Life and Times of Takabuti in Ancient Egypt: Investigating the Belfast Mummy.

But the most remarkable discovery came from her DNA. In 2020, scientists published “The first reported case of the rare mitochondrial haplotype H4a1 in ancient Egypt” (Drosou et al., 2020), revealing that Takabuti belonged to mtDNA haplogroup H4a1—a lineage rare in both modern and ancient populations. This haplogroup has appeared sporadically in regions such as southern Iberia, the Canary Islands, Lebanon, and Bronze Age Europe, but had never before been identified in Egypt.

The finding suggested complex patterns of ancient movement and interaction between North Africa and the Mediterranean, centuries before the Greek or Roman presence in Egypt. Takabuti’s story now stands as both a testament to early museum curiosity and a reminder that ancestry often crosses borders we never imagined.

Today, Takabuti still rests in the Ulster Museum, where modern analysis continues to shed new light on her life, death, and the unexpected diversity of ancient Egypt’s genetic landscape.

Ancient North American Mummies: Preserved by Time and Earth

From the scorching deserts of Nevada to the rugged mountains of northern Mexico, the first mummies of North America were not created by human hands—but by nature itself. In dry caves and high plateaus, arid air and mineral-rich soil halted decay, preserving bodies that would one day help unlock the continent’s oldest genetic stories.

Unlike Egypt’s ritual burials, these mummies were naturally preserved, their survival owed to climate rather than ceremony. Yet through modern DNA analysis, their remains have become just as revealing, connecting ancient individuals to living descendants and tracing migrations that shaped the earliest chapters of the Americas.

Both the Spirit Cave Mummy of Nevada and Momias de México 6 from the Sierra Tarahumara share not only preservation by aridity, but ancestry through the Q-haplogroup lineages—a paternal branch tracing back over 15,000 years to the first peoples who crossed from Siberia into the New World. Together, they reveal how environment and lineage worked hand in hand to preserve stories once thought lost to time.

Spirit Cave Mummy — Haplogroup Q-Y166185: The Oldest Mummy Ever Found

In the summer of 1940, husband-and-wife archaeologists Sydney and Georgia Wheeler explored a series of caves in Churchill County, Nevada, searching for evidence of early human life near the receding shores of prehistoric Lake Lahontan. Among their discoveries was a remarkably preserved individual later known as the Spirit Cave Mummy. At the time, the remains were believed to be around 2,000 years old and were carefully stored at the Nevada State Museum.

More than fifty years later, scientists re-examined the mummy using accelerator mass spectrometry (AMS) radiocarbon dating on samples of bone and hair. The results were groundbreaking: the Spirit Cave Mummy was more than 9,400 years old, making it the oldest mummy ever discovered in North America, according to the Archaeological Institute of America (1996).

The mummy’s remarkable preservation was due to natural mummification from the heat and aridity of the cave. Later DNA analysis identified the individual’s Y-DNA haplogroup as Q-Y166185, revealing a deep genetic connection to the earliest ancestors of modern Native American populations. This discovery reshaped scientific understanding of migration and settlement patterns across the Americas.

The story didn’t end there. Following decades of discussion over cultural identity, the Fallon Paiute-Shoshone Tribe sought recognition of the individual as their ancestor. In 2016, after DNA confirmed the connection, the remains were repatriated and reburied according to tribal tradition—a rare moment where science and cultural respect met in harmony.

Nearly 10,000 years later, the Spirit Cave Mummy reminds us that ancient DNA can reveal connections that time alone could never erase.

Momias de México 6 — Haplogroup Q-CTS10359: Threads Between Worlds

High in the Sierra Tarahumara mountains of Chihuahua, Mexico, the individual known as Momias de México 6 (MOM6) offers a rare glimpse into the ancestry of ancient Mexico. While the exact details of his original burial are unknown, his remains were later preserved and curated in the Museo Nacional de Antropología in Mexico City as part of the Momias de México collection.

In 2015, researchers led by Maanasa Raghavan included MOM6 in a groundbreaking genetic study, confirming that his tissue was authentic pre-Columbian mummy material. DNA extracted from a tooth revealed connections that reach back thousands of years, linking him to some of the earliest populations of the Americas.

A later 2022 study by Viridiana Villa-Islas and colleagues found that MOM6 carried Mesoamerican and Aridoamerican ancestry. Mesoamerica refers to the agricultural civilizations that thrived in central and southern Mexico—such as the Maya, Zapotec, and Mexica (Aztec). Aridoamerica encompassed the desert cultures of northern Mexico and the U.S. Southwest, known for their resilience and nomadic traditions. This genetic mix reflects how ancient peoples traded, traveled, and built relationships across these vast cultural frontiers.

When compared to modern populations, MOM6 clustered most closely with Purépecha and Nahua communities from Jalisco, suggesting ancestral roots in central-west Mexico despite his northern resting place. His paternal lineage, Y-DNA haplogroup Q-CTS10359, traces back more than 15,000 years to the first migrations from Siberia into the Americas, a lineage still widespread among Indigenous peoples today.

Though MOM6’s story is missing many pieces, his DNA preserves a rare genetic snapshot of Mexico’s deep diversity and shines a light on the bridge between the desert cultures of the north and the temple cities of the south.

And while MOM6 himself isn’t on public display, travelers can still explore Mexico’s mummified history at the Museo de las Momias de Guanajuato, home to one of the world’s largest and most haunting collections of naturally preserved remains.

Mummies Found in Peru and the Andes: Echoes in Thin Air

From the high peaks of the Andes to the arid deserts along Peru’s northern coast, South America holds some of the world’s most breathtaking examples of ancient preservation. Here, thin air, cold temperatures, and ritual devotion combined to create natural and ceremonial mummies whose DNA still speaks across millennia.

Unlike the elaborate burials of Egypt, many Andean mummies were preserved by the mountains themselves—frozen by altitude or wrapped in desert sands. Each one offers a window into the beliefs, power, and ancestry of pre-Columbian civilizations that flourished long before European contact.

In this section, we’ll look at two of the region’s most remarkable discoveries: the Aconcagua Mummy, a young Inca boy sacrificed high in the Argentine Andes, and the Señora de Cao, a noblewoman from ancient Peru whose tattoos and DNA revealed the influence—and complexity—of women in Moche society.

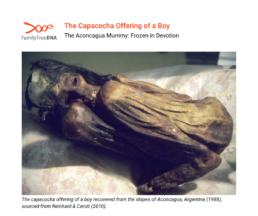

The Aconcagua Mummy — Haplogroups Q-Y166275 (Y) and C1b (mtDNA): Frozen in Devotion

In 1985, a group of mountaineers scaling Mount Aconcagua in Argentina stumbled upon something extraordinary—a small body, frozen at an altitude of 5,300 meters (17,400 feet) near the base of the Pirámide peak. When archaeologists returned to excavate the site, they uncovered a remarkably preserved seven-year-old boy from the Inca civilization, wrapped in 18 layers of fine textiles and surrounded by six small figurines.

The child was a victim of capacocha—a ritual sacrifice practiced by the Inca roughly 500 years ago to honor their gods during times of crisis or major imperial events. Children of exceptional health and beauty were chosen from across the vast empire, brought to Cusco for ceremonies, and then carried to mountaintop shrines to become eternal messengers to the divine.

Preserved by altitude and ice rather than time and tomb, the Aconcagua Mummy remains one of the most haunting archaeological discoveries in the Andes. His burial, situated near the empire’s southernmost frontier, marked the outer edge of Inca expansion into what is now Argentina.

Genetic analysis of tissue samples has revealed his Y-DNA haplogroup Q-Y166275 and mtDNA haplogroup C1b, both lineages tracing to central Peru and still found among modern Quechuan-speaking populations, including the Choppca people. His DNA supports historical records suggesting he was brought from Peru to the Andes for the capacocha ceremony—a journey of hundreds of miles undertaken in the name of faith and empire.

This young boy’s frozen form tells a story both heartbreaking and illuminating: a glimpse into how the Inca connected the physical and spiritual worlds, and how DNA continues to bridge the distance between the living and the long departed.

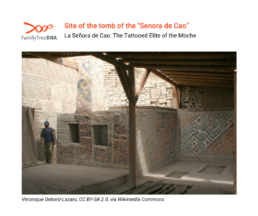

La Señora de Cao — Haplogroup D (mtDNA): The Tattooed Elite of the Moche

In 2006, archaeologists led by Régulo Franco Jordán uncovered a stunning discovery within the Huaca Cao Viejo temple at the El Brujo Archaeological Complex in northern Peru. Wrapped in 25 layers of fine cotton and adorned with gold ornaments, crowns, and ceremonial weapons, lay the remains of a young woman whose tattoos of snakes, spiders, and lunar creatures shimmered faintly beneath her skin. She became known as La Señora de Cao—the Lady of Cao—and her discovery forever changed what we know about power, gender, and divinity in ancient Peru.

Dating to around 440-540 CE, the Lady of Cao belonged to the Moche civilization, a culture that flourished along Peru’s northern coast between the 4th and 10th centuries CE. Her elaborate burial, complete with regalia typically reserved for male rulers, revealed her as one of the first confirmed female leaders in pre-Columbian South America. Her tattoos—crafted with remarkable precision—depict animals sacred to the Moche worldview and symbolize fertility, protection, and lunar power.

Bioanthropological studies show she stood just under one and a half meters tall (just under five feet) and died in her mid-twenties, likely from complications during pregnancy or childbirth. Despite her youth, her insignia—diadems, nose rings, and war clubs—mirror those seen in Moche iconography of elite rulers, suggesting she held both political and spiritual authority.

Recent research has deepened her story. In 2024, John Quilter and colleagues analyzed DNA from six elite burials found alongside the Lady of Cao. The study revealed that all six individuals were biologically related, supporting the theory that kinship was central to maintaining power among Moche elites. The Lady herself was interred with a sacrificed juvenile—possibly her niece—and several relatives buried nearby, including at least one sibling and a grandparent. This blending of family and ritual underscores how deeply the Moche linked bloodlines, sacrifice, and divine legitimacy.

Her mitochondrial DNA belongs to haplogroup D, a lineage widely found among Indigenous peoples of the Americas. This connects her to living descendants across the continent, transforming her from an isolated archaeological wonder into part of a broader genetic story.

Today, La Señora de Cao rests at the Museo Cao, her body preserved under glass beside a lifelike reconstruction of her face. Visitors stand before her not just as a ruler of the past, but as a symbol of resilience, leadership, and the enduring power of women in history.

Frozen in Time: European Mummies and Ancient DNA (Europe)

Europe’s most famous mummy isn’t wrapped in linen or sealed in a tomb—he’s frozen in ice.

In the heart of the Alps, natural preservation rather than ritual mummification has kept one Copper Age man astonishingly intact for more than 5,000 years. Known today as Ötzi the Iceman, his discovery revealed a remarkably complete glimpse into prehistoric European life, diet, and DNA.

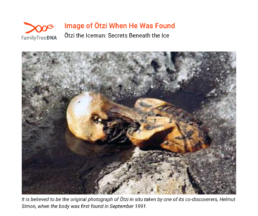

Ötzi the Iceman — Haplogroups G-L166 (Y) and K1d’k (mtDNA): Secrets Beneath the Ice

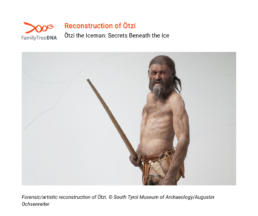

In September 1991, two hikers, Helmut and Erika Simon, discovered what they thought was the body of a lost mountaineer near the Tisenjoch Pass in the Ötztal Alps, straddling the border of Austria and Italy. What they had actually found was one of the world’s best-preserved mummies—Ötzi, a man who had lain frozen in the ice for more than 5,300 years.

Ötzi’s body, clothing, and tools were nearly intact, preserved by the glacial cold of the Copper Age. Researchers recovered his axe, bow, quiver, and even the remnants of his last meal. An arrowhead lodged in his left shoulder revealed the true cause of death: a fatal wound that shattered his scapula and likely caused him to bleed to death, making his death one of history’s oldest unsolved murders.

Genetic sequencing conducted in 2012 revealed that Ötzi carried Y-DNA haplogroup G-L166 and mtDNA haplogroup K1d’k, lineages still found today in Europe and around the Tyrrhenian Sea—particularly among populations in Sardinia and Corsica. His genome also provided astonishing insights into his health and appearance. He had:

- brown eyes

- blood type O

- lactose intolerance

- a genetic predisposition to heart disease.

Researchers even identified fragments of the bacterium Borrelia burgdorferi, making him the earliest known case of Lyme disease in humans.

Beyond genetics, his discovery transformed the study of prehistoric Europe. Every item he carried, from birch-bark containers to a copper axe, spoke to a sophisticated and resourceful society at the dawn of metallurgy. Today, Ötzi rests in the South Tyrol Museum of Archaeology in Bolzano, Italy, where he continues to reveal secrets frozen in time.

Ancient Mummies of Oceania and Asia

From the sun-bleached cliffs of Queensland to the frozen steppes of Siberia, the story of mummification spans far beyond Egypt’s sands. In these regions, vastly different environments, and equally distinct cultures, found their own ways to preserve the dead.

In Oceania, Indigenous Aboriginal Australians like King Ng:tja practiced ceremonial preservation that honored ancestry and spiritual connection to the land. Thousands of miles north in Asia, the Tashtyk people of southern Siberia created intricate mummified effigies, blending artistry, ritual, and migration. Together, these discoveries reveal that across continents, humanity has always sought to keep its ancestors close—whether through sacred ceremony or the silent work of ice and time.

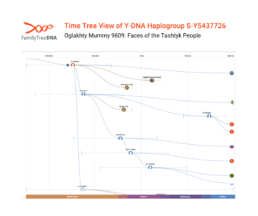

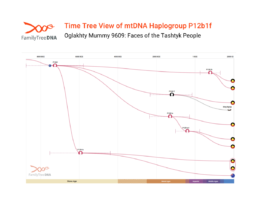

King Ng:tja — Y-DNA Haplogroup S-Y543772 | mtDNA Haplogroup P12b1f: The Aboriginal King Who Came Home

Among the red earth and rainforest canopies of Queensland’s Atherton Tablelands, the story of King Ng:tja (also known as Nacha, Naicha, or Barry Clarke) stands as both a scientific discovery and a moral reckoning. A revered leader of the Ngadjon-Jii people, King Ng:tja passed away in 1903. Following the sacred funerary traditions of his community, his body was ceremonially mummified.

A year later, his peace was broken. In 1905, Herman Klaatsch, a German-born anthropologist, journeyed across northern Australia to study Indigenous remains. His methods, common for the colonial era but deeply unethical by today’s standards, included the removal of King Ng:tja’s mummified body — bound in a crouched position and wrapped according to Ngadjon-Jii custom. The mummy was taken first to Sydney’s Australian Museum, then shipped to Berlin, where it was displayed for decades at the Berlin Society for Anthropology, Ethnology, and Prehistory.

After more than a century abroad, justice finally came. In 2017, King Ng:tja’s remains were repatriated to Australia — the first known return of a mummified body to its Indigenous descendants. His family and community held a smoking ceremony at the Queesnland Museum Tropics in Townsville restoring the dignity and cultural connection that had been severed for generations.

In 2024, King Ng:tja’s name resurfaced not in scandal, but in science. His remains were included in the study “Genetic Predisposition of Atherosclerotic Cardiovascular Disease in Ancient Human Remains” (Wurst et al., 2024), where his DNA revealed the ancient Y-DNA haplogroup S-Y543772 and mtDNA haplogroup P12b1f — both uniquely Australian Aboriginal lineages. These findings affirmed what Indigenous knowledge has always held true: that Aboriginal Australians are among the world’s oldest continuous cultures, with genetic roots reaching back over 50,000 years.

Today, King Ng:tja’s story bridges worlds — science and spirit, colonial harm and cultural healing. His journey home reminds us that even when history’s silence feels heavy, DNA can still speak truth across centuries.

Oglakhty Mummy 9609 — Y-DNA Haplogroup R-Y39884 | mtDNA I4a1: Faces of the Tashtyk People

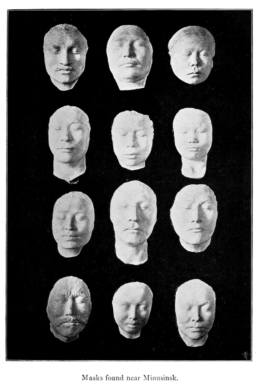

Beneath the frozen steppes of southern Siberia, in the Minusinsk Basin, archaeologists uncovered a world both haunting and beautiful: the Oglakhty cemetery, a burial ground belonging to the Tashtyk culture—a mysterious post-Scythian people who flourished between the 2nd and 4th centuries CE.

Here, the dead were treated with remarkable care. Some were mummified and laid within life-size leather and grass mannequins; others were cremated, their ashes placed inside painted effigies with human faces. Many wore finely woven textiles or masks of plaster and gypsum—creations so lifelike they seem to watch the living across centuries.

In 2022, researchers performed the first ancient-DNA analysis of these mummies (Nedoluzhko et al., 2022). Among them, Individual 9609 revealed Y-DNA haplogroup R-Y39884, a branch of R1a common among Eurasian steppe populations, and mtDNA I4a1, a rare lineage with European connections. Together, these results reflected what the Tashtyk graves already suggested: this was a culture born of contact—where the Indo-European west and Siberian east intertwined.

Archaeological evidence from Oglakhty shows that the Tashtyk people lived in small, kin-based groups, combining pastoralism, hunting, and limited agriculture. Their burial customs—at once intimate and theatrical—hint at a worldview where life and death coexisted. The arid, sheltered conditions of the Minusinsk Basin preserved these remains in astonishing detail, from the delicate stitching of garments to the painted eyelashes on funerary masks.

Through DNA, these ancient artisans have rejoined the human story. Their genomes bridge Europe and Central Asia, showing how migration, trade, and artistry converged in Siberia’s heartland. Even now, under the frozen soil of the Yenisei River valley, their silent faces remind us that ancestry often transcends the borders we draw today.

How Are Mummies Preserved and How Does DNA Survive?

Not all mummies are made the same way. Some, like Egypt’s royal burials, were deliberately preserved through ritual embalming, where organs were removed, the body was dried with natron, and wrapped in layers of linen. Others, like the Spirit Cave Mummy or Ötzi the Iceman, were preserved by nature itself when intense heat, cold, or dryness stopped decay in its tracks. Whether deliberate or accidental, mummification depends on one thing above all: an environment harsh enough to silence the microbes that would normally return us to dust.

Even after thousands of years, those same conditions can protect tiny fragments of ancient DNA. While FamilyTreeDNA doesn’t sequence these remains directly, our scientists analyze the genetic data recovered. By placing those results alongside living testers in our database, we continue to grow a single, interconnected tree, rooted in the present but reaching deep into the ancient past.

Are Mummies Dangerous or Cursed?

For all the talk of “mummy’s curses,” the truth is far less deadly—and far more interesting. Real mummies aren’t zombies waiting to rise from the tomb; they’re time capsules of ancient life. The only thing that “comes back to life” is their DNA, reawakened through modern genetic analysis that helps us understand who they were and how their lineages connect to ours today.

Want to see which ancient line you might connect to? Take a Y-DNA or mtDNA test and explore your results in the Discover haplogroup reports.

Frequently Asked Questions About Mummies and DNA

Q: Do mummies still have DNA?

A: Yes — in some cases. When conditions like extreme dryness, cold, or intentional embalming prevent decay, tiny fragments of DNA can survive for thousands of years. Scientists can analyze this ancient genetic material to study ancestry, migration, and population history.

Q: What is the oldest mummy with DNA?

A: The Spirit Cave Mummy from Nevada—dated to around 9,400 years old—is one of the oldest known naturally preserved remains with recoverable DNA. Its genetic profile helped confirm early population connections between ancient and modern Indigenous peoples of the Americas.

Q: Can you share a haplogroup with a mummy?

A: Absolutely. If your Y-DNA or mtDNA haplogroup matches one identified in an ancient individual, you share a direct paternal or maternal ancestor who lived thousands of years ago.

Q: Are mummies fossils?

A: No. Fossils form when organic material is replaced by minerals over millions of years, leaving behind stone-like remains. Mummies are preserved bodies, often with skin, hair, and soft tissue intact—kept from decaying by intentional embalming or natural conditions.

Q: How long can mummies last?

A: Under the right conditions, mummies can survive for thousands of years. Some, like Egypt’s royal mummies or the Spirit Cave Mummy in Nevada, remain remarkably intact thanks to dry air, stable temperatures, and protection from bacteria.

Q: What makes mummies important to science?

A: Mummies preserve more than bones—they hold ancient DNA, artifacts, and cultural clues that help researchers understand how people lived, traveled, and evolved. Each mummy connects us more deeply to human history through both genetics and archaeology.

About the Author

Courtney Eberhard

Senior Marketing Specialist

Courtney is driven by a profound passion for genealogy, fueled by her personal journey as an adoptee with roots in the LDS church. Through research with FamilyTreeDNA, she has also been able to uncover her son’s father’s indigenous roots in Mexico and provide context for his origins.

In her spare time, she finds joy in connecting with her family and friends during cookouts, cheering for the Houston Astros, and cherishing her role as a dedicated full-time parent.

I already have done the Y DNA. Tell me what to do next. This mummy thing sounds like a fascinating thing to check out.

Hi Millie!

Have you visited our Discover site?