By: Andrew Hochreiter

From my Bavarian roots to a surprising Mediterranean haplogroup, I traced my German ancestry through phone records, surname studies, and Y-DNA testing.

In a previous blog I described how I found seventh cousins living in Germany. During the short time since this article, FamilyTreeDNA has implemented valuable new tools that provide fresh insight into my Germanic paternal side inheritance. The introduction of the Discover™ tools has heightened my understanding of both my patrilineal deep roots, as well as the recent family branching.

Discovering My German Heritage in Bavaria

I was fortunate that my German immigrant ancestors were recent arrivals, and their home village was preserved in living memory. They came from the northern Bavarian market town of Moosbach, located east of Nuremberg and about 10 kilometers from the Czech border.

Using the Catholic Church records at the Bishop’s Archives in Regensburg, I traced my Hochreiter ancestors to Johann Hochreutter, 1658-1719.

Unfortunately, church accounts for earlier Hochreiters don’t exist, probably casualties of the Thirty Years War that claimed lives, property and records of both Protestant and Catholic combatants.

But as a result, I became intrigued in the deeper roots of my family and the relationship to other Hochreiters living in Europe. How long did Hochreiters live in my ancestors’ homestead village or this area of Germany? How are they related to Hochreiters currently living elsewhere in Germany or other countries?

Just as etymology studies the historical origin of words, onomastics studies the origins of names, including surnames. The spelling of the Hochreiter surname varied in documents but derives from common Germanic roots. The spellings include:

- Hochreiter

- Hochreuter

- Hochreuther

- Hochreutter

- Hochreitter

This is due to the non-standardization of spelling among the clerks and clergy who recorded the documents. Translated from German the name Hochreiter literally means “high or tall” (hoch) and “rider or horseman” (reiter). This meaning sounds like an occupational name such as a tall horseman.

Despite the hope of a noble adoption of this surname from an ancestral knight, the reality is more commonplace. Surname dictionaries relate the name Hochreiter to Hochreuter.

The Dictionary of American Family Names reports that the surname “Hochreiter” is from the “South German: a topographic name for someone who lived on or owned a piece of high-lying cleared land, from Middle High German hohe “high” + riute “cleared land” + the agent suffix –er.”

So, my ancestors were obviously farmers who enjoyed their beer with a view from the hillside!

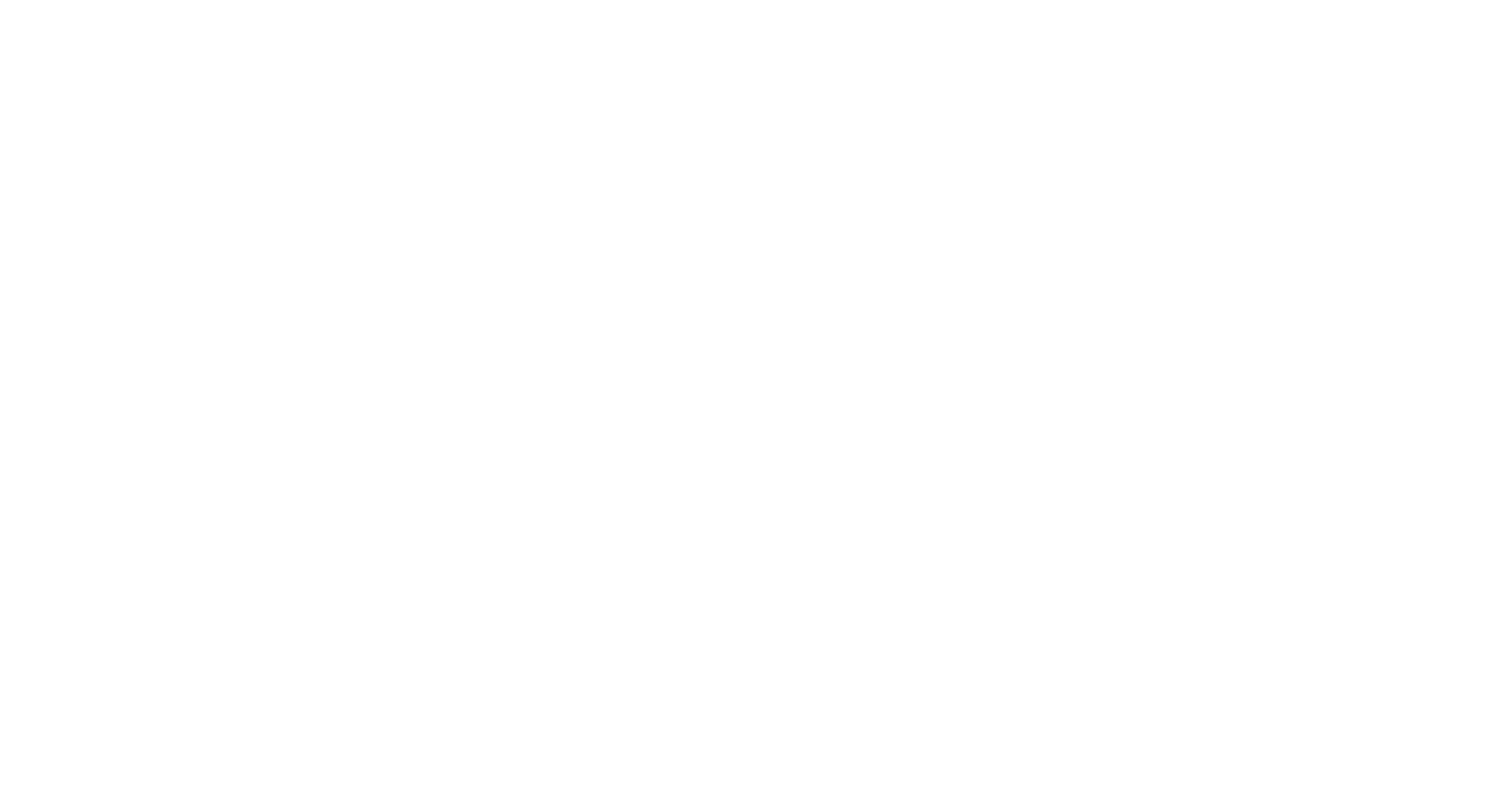

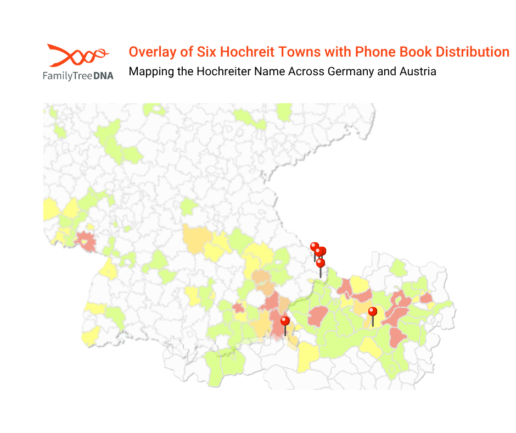

A theory for the ending “er” is that the name was for an individual “from or of” the village of Hochreut or Hochreit. Along this line of thought, there are three small villages named Hochreut located in southern Germany at postal zones:

- 94065 Waldkirchen

- 94143 Grainet

- 94130 Obernzell

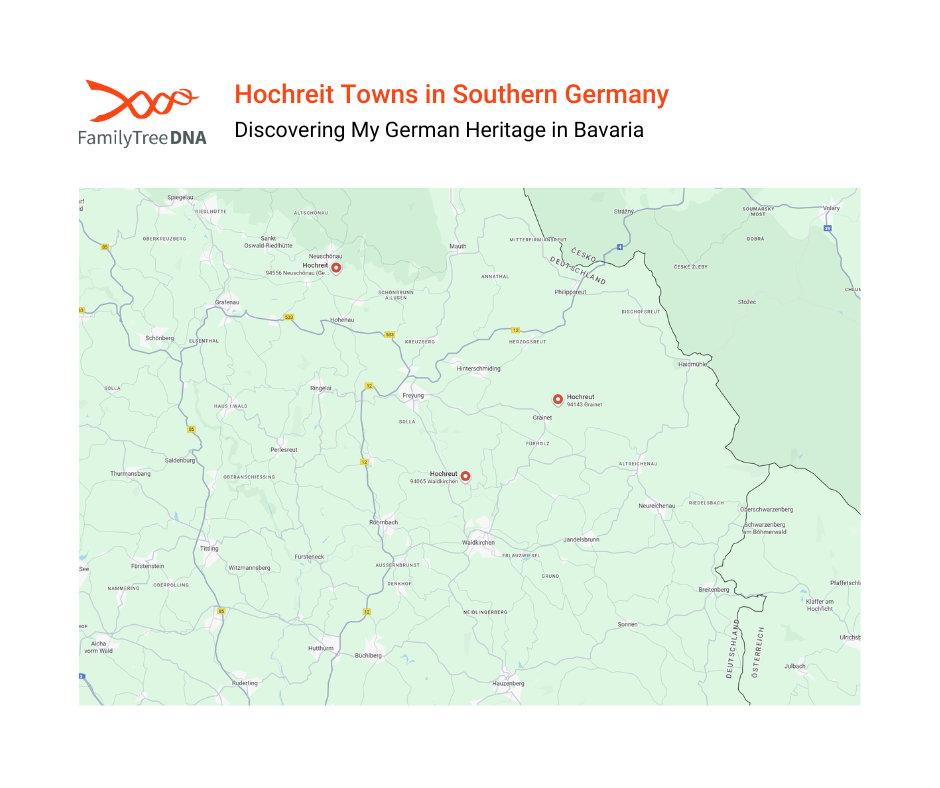

There are also three villages named Hochreit, one in southern Germany and two in northern Austria:

- 94556 Neuschönau (Germany)

- 3345 (Salzburg)

- 5091 (Lower Austria)

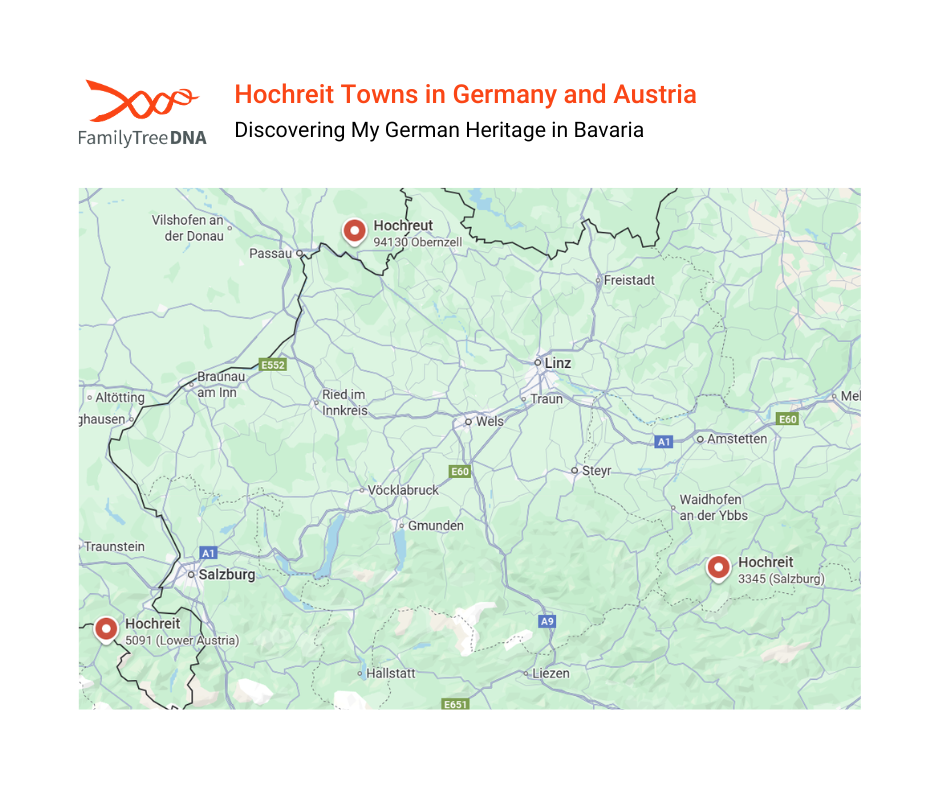

Mapping the Hochreiter Name Across Germany and Austria

Using previous access to online telephone listings, I identified the various locations in hopes of determining lines and relationships. Launching the Y-DNA Hochreiter Surname Project at FamilyTreeDNA was the start of this search for common roots and origins.

Although there are no longer any Hochreiters who reside in Moosbach, I was initially encouraged that there were multiple listings for Hochreiter families in the online German telephone books. I used these resources to investigate other unknown families and locations, which helped to understand the demographics of where Hochreiter spelling variations were clustered in Germany and Austria.

The dispersal of the surname is wider than I first suspected but is more predominant in the Alpine areas of Germany.

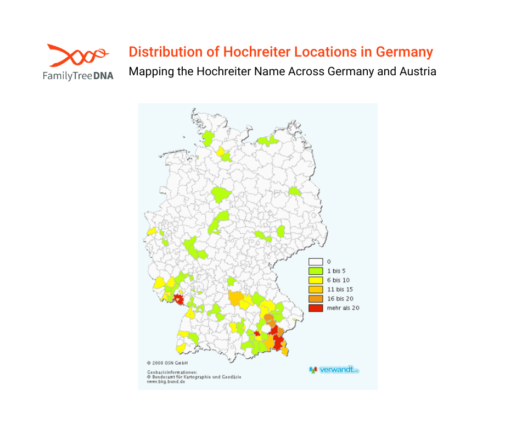

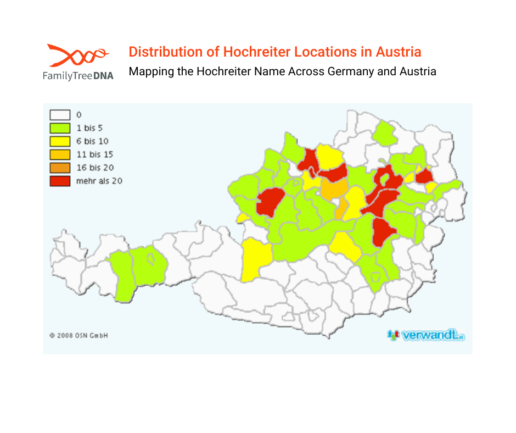

Using various resources, such as telephone and surname collection sites, I compared the range and number of people with this surname in different regions. The following maps came from a defunct website verwandt.de. The site provided the distribution of Hochreiter locations in Germany based on their telephone listings.

Although I use the present tense, these statistics were gathered several years ago so may have changed.

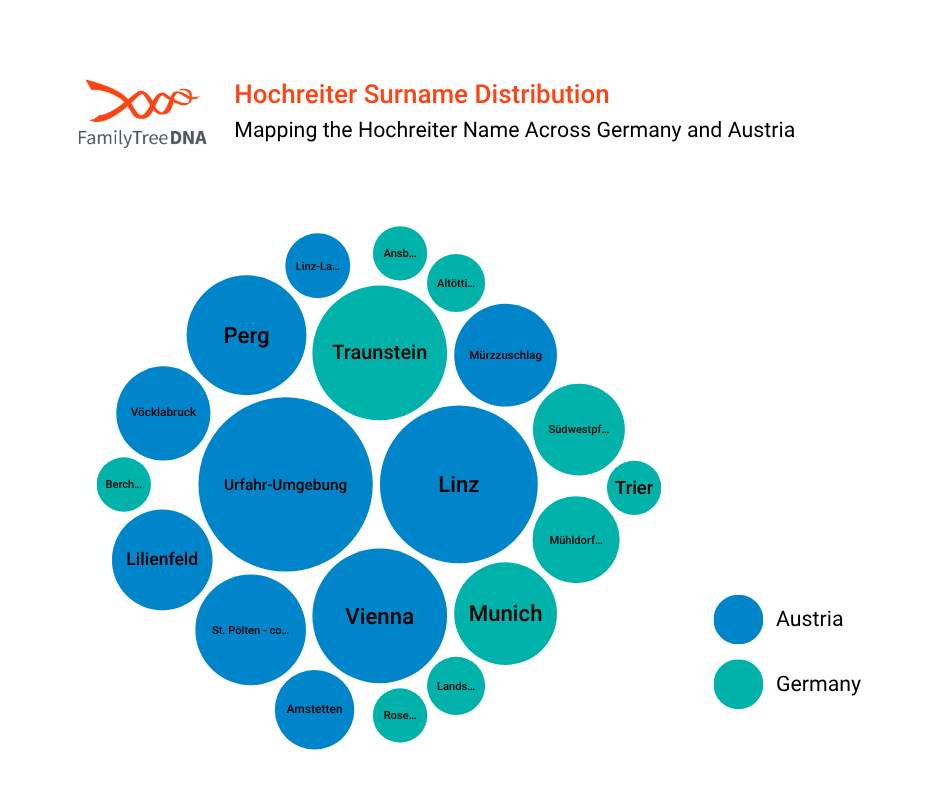

In Germany there are 277 phone book entries with the surname Hochreiter, which estimates approximately 738 individuals with this name in Germany. They live in 74 cities and counties, with most in:

- Traunstein (43)

- Munich (25)

- Südwestpfalz (20)

- Mühldorf am Inn (18)

- Altötting (8)

- Landshut (8)

- Berchtesgaden (7)

- Trier (7)

- Rosenheim (7)

- Ansbach (7)

Austria has a larger number of Hochreiters than other European countries including Germany. In Austria there are 461 phone book entries with the surname Hochreiter and approximately 631 persons with this name. It is the 517th most frequent name in Austria. They live in 46 cities, most are in:

- Urfahr-Umgebung (72)

- Linz (59)

- Vienna (43)

- Perg (34)

- St. Pölten – country (29)

- Mürzzuschlag (25)

- Lilienfeld (24)

- Vöcklabruck (21)

- Amstetten (15)

- Linz-Land (10)

The distribution of Hochreiter reflects its German roots with a concentration in Austria and Germany, but a small scattering of Hochreiter listings is found in other countries, namely:

- Switzerland

- Slovakia

- Czech Republic

- Poland

- Hungary

There is one person with the surname Hochreiter in Nowy Targ, Poland. In Switzerland there are 2 telephone book entries with an estimate of around 5 people total in this country. I did not find any listings in any of the Balkan countries.

What My DNA Revealed About My German Ancestry

One of the great attractions of autosomal DNA (atDNA) testing is the ethnicity and admixture report offered in the DNA results. Although results vary widely between test companies based on their reference populations, algorithms, and threshold standards, ethnicity reports are a popular aspect for almost everyone.

Depending on one’s knowledge of genetic genealogy and understanding of its randomness, we generally expect an alignment with our family’s ethnic history, identity, and documentation. Autosomal DNA is our source for identification of recent ancestry, despite the complications of NPEs, endogamy and mixing of national/ethnic populations.

For myself, I find a general consistency of my maternal British roots and paternal Germanic roots. Family Finder confirms the division of my atDNA between my British and Germanic ancestry. But this admixture is reflective of a recent genealogically relevant period. With the dissipation of ancestral contributions from our atDNA profile, we miss the story of our ancient roots that is not preserved in our 44 autosomes. That is why our Y-chromosomal and mitochondrial DNA is also so valuable to our family histories. In this respect, examining my Y-DNA provides additional findings to my identity of German ancestry.

One of the great surprises of my Y-DNA testing was the confirmation that my patrilinear haplogroup was considered Mediterranean. My very-German surname and known ancestral location in Germany made me anticipate a northern European Y-DNA Haplogroup. But my Y-DNA test revealed E1b1b1a2 under the old nomenclature designation, which surprisingly showed Mediterranean or southern European origins. This haplogroup did not square with my idea of a German identity, but it motivated me to try to reach back farther to discover how I wound up German.

My surname project started in 2007 for men who carry the Hochreiter surname or variations such as Hochreuter and Hochreither. Although the project is not large, there are participants from various US states, Germany, Hungary, Slovakia, and Austria. I began testing many of my known male relatives including first and second cousins. This established a DNA signature to compare to other unknown participants. All my relatives who descend from Moosbach immigrants belong to Y haplogroup E1b.

I began a recruitment campaign by downloading address lists from online telephone books and befriending every Hochreiter on Facebook. As I tested more unknown Hochreiters, I found that none of them matched my family’s Y-DNA. Currently we have participants represented by Y haplogroups R1a (western Europe), R1b (central & eastern Europe), N (northern Eurasia), and L (south Asia). Despite a common surname, it was obvious that it was adopted by unrelated families. A very promising discovery was a Hochreiter beer tent at the famous Oktoberfest. The proprietor agreed to test, but the results were the Y-DNA haplogroup N. Imagine my disappointment not to claim a relationship to an Oktoberfest vendor and patron!

I eventually found a related branch of Hochreiters in Germany and the USA who shared the same E1b Haplogroup. Their origins go back to a common ancestor named Johann Hochreutter (1681-1752) in Moosbach. But the mystery of our earlier origins remained.

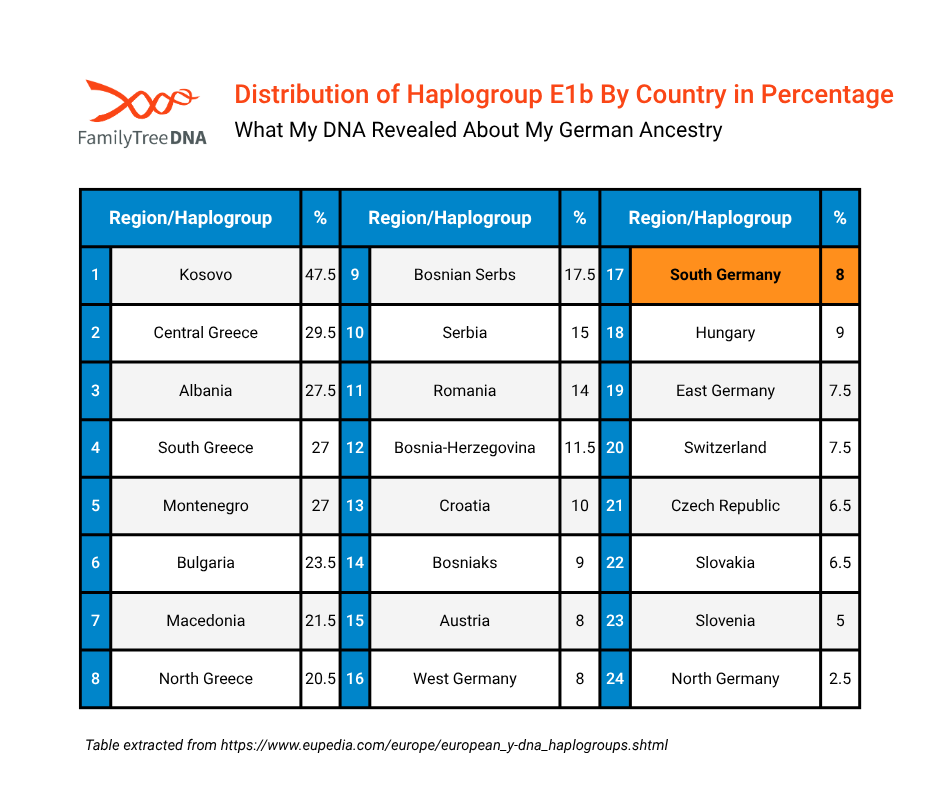

So, I began to research how my ancestors may have first come to Germany. I looked for clues in my Y-DNA. It became evident that the evolution of my haplogroup followed a path of mutations out of Africa, the Middle East and Anatolia into the Balkans and Eastern Europe. The presence of E1b in South Germany (Bavaria, in my case) is 8% of the population.

This list from Eupedia.com may be somewhat outdated but still demonstrates the concentration of my Y-DNA Haplogroup along a diaspora out of Africa along a track eventually into Germany. The percentage of E1b is remarkably high in many Balkan countries. It’s the highest in Kosovo, Greece and Albania, and fades in proportion as it moves north through Eastern Europe to Germany. It is estimated that a major branching of the E1b group occurred in the Balkans region with the mutation E-V13 (E1b1b1a1a1a).

“In fact, it has been calculated that E-V13 emerged from E-M78 some 7,800 years ago, when Neolithic farmers were advancing into the Balkans and the Danubian basin. Furthermore, all the modern members of E-V13 descend from a common ancestor who lived approximately 5,500 years ago, and all of them also descend from a later common ancestor who carried the CTS5856 mutation. That ancestor would have lived about 4,100 years ago, during the Bronze Age. Almost immediately afterwards, CTS5856 split into six subclades, then branched off into even more subclades in the space of a few generations.”

Using the Big Y-700 Test to Deepen My Ancestry Research

The research on my family was bolstered with the Big Y-700 test. It reaffirmed many of the previous findings with more granularity and explanation. Most importantly, it brought back the ancient origins into the genealogically relevant timeframe. The explosive discoveries and advancement of SNP markers has refined our assumptions into remarkable indicators of time, location, and relationship.

Each of the new Discover haplogroup reports add value to my family research, but a few deserve more recognition.

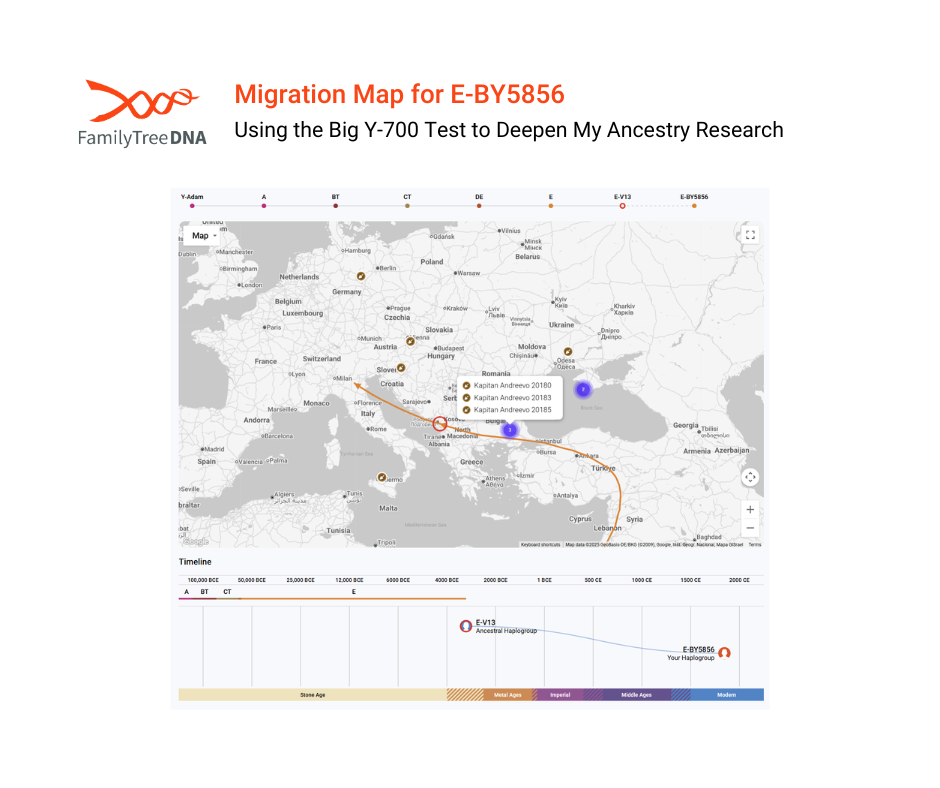

Following My Ancestors’ Migration Path

The Migration Map in FamilyTreeDNA’s Discover reports gives a visual snapshot of overlapping aspects of my genetic story.

What it shows:

-

- The route of my Y-DNA haplogroup mutations

- Ancient DNA discoveries tied to my lineage

- Clusters in the Balkan region that suggest how my E1b ancestors may have journeyed into Germany

Together, these elements provide a geo-timeline of migration—from early origins in Africa, through the Middle East and Anatolia, across the Balkans, and finally into Bavaria. This map helped me connect the movement of my distant ancestors with the story of my own German heritage.

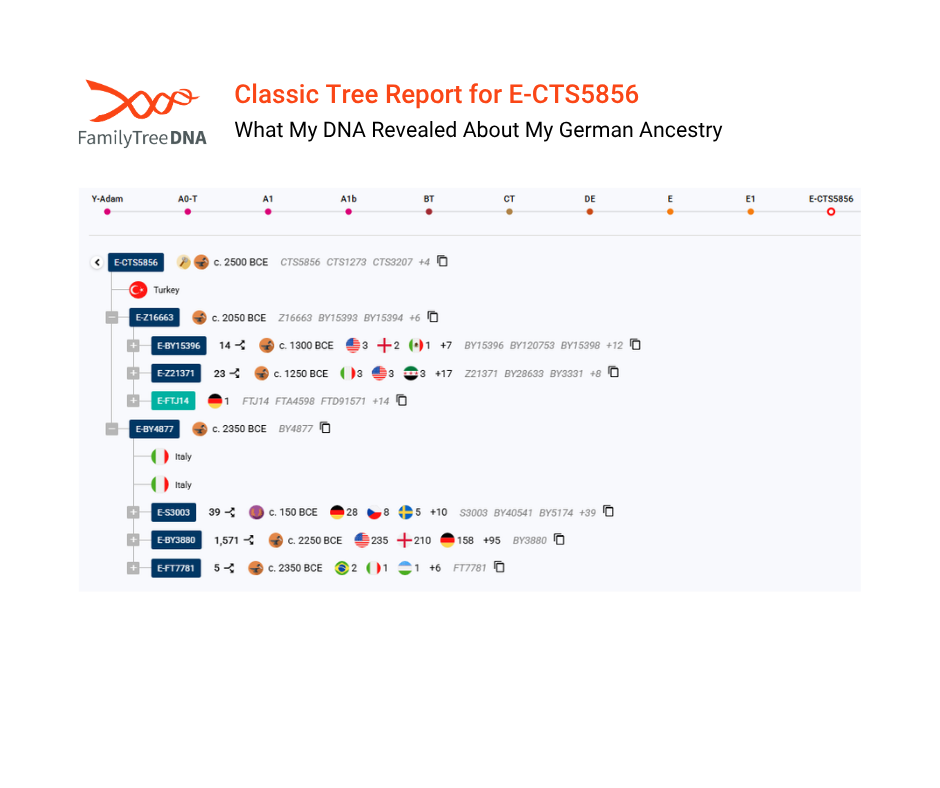

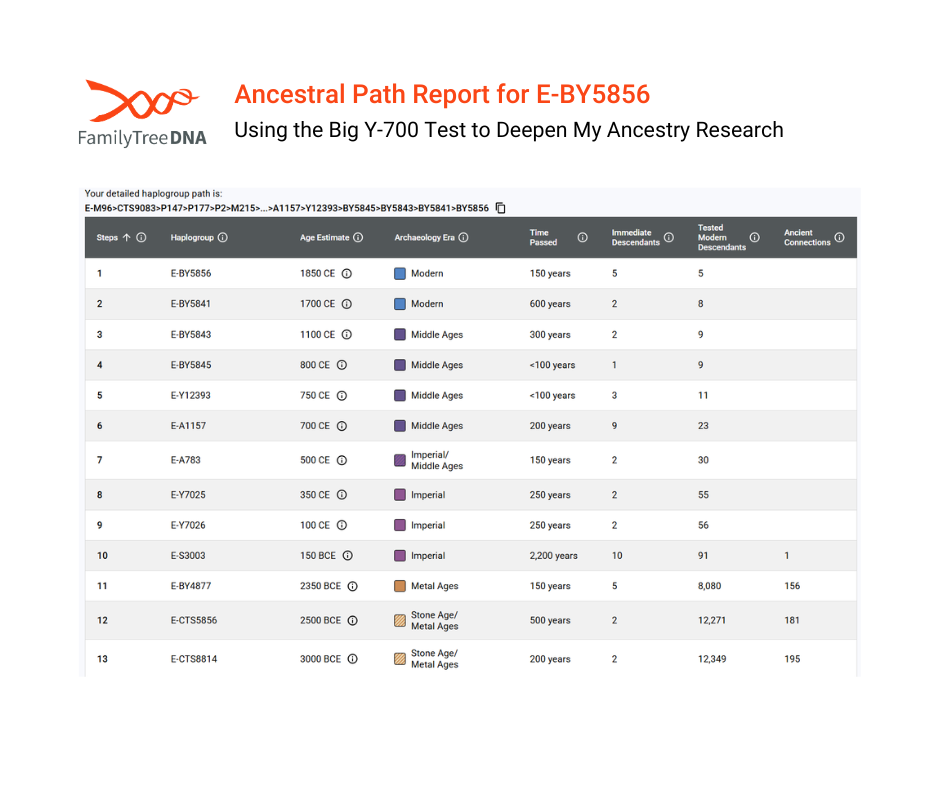

Tracing My Genetic Line Through the Ancestral Path Report

The Ancestral Path feature in Discover™ lays out a detailed sequence of mutations leading to my terminal SNP.

What it shows:

-

-

- A chronological path beginning with Y-Adam (~100,000 BCE)

- Each known mutation along my lineage to the present

- The estimated year that my most recent ancestor acquired the latest mutation (E-BY5856, around 1850)

-

This visual timeline makes thousands of years of genetic change easier to follow. Seeing my family’s branch stretch from deep prehistory to a named ancestor reminded me that even the most ancient DNA results can tell a very human story.

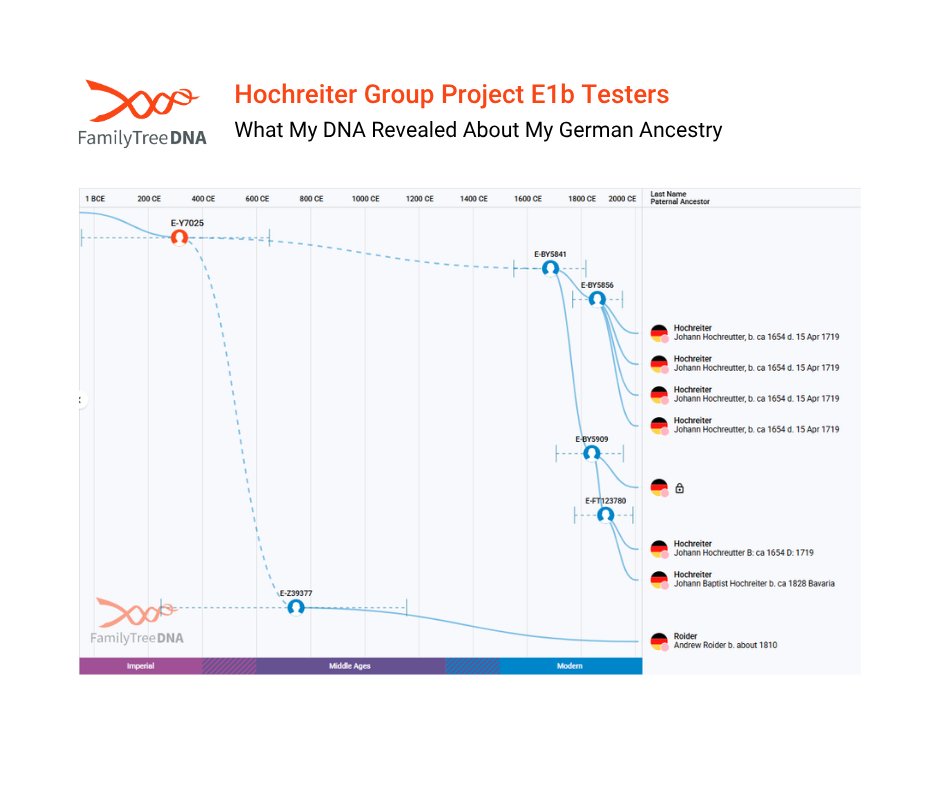

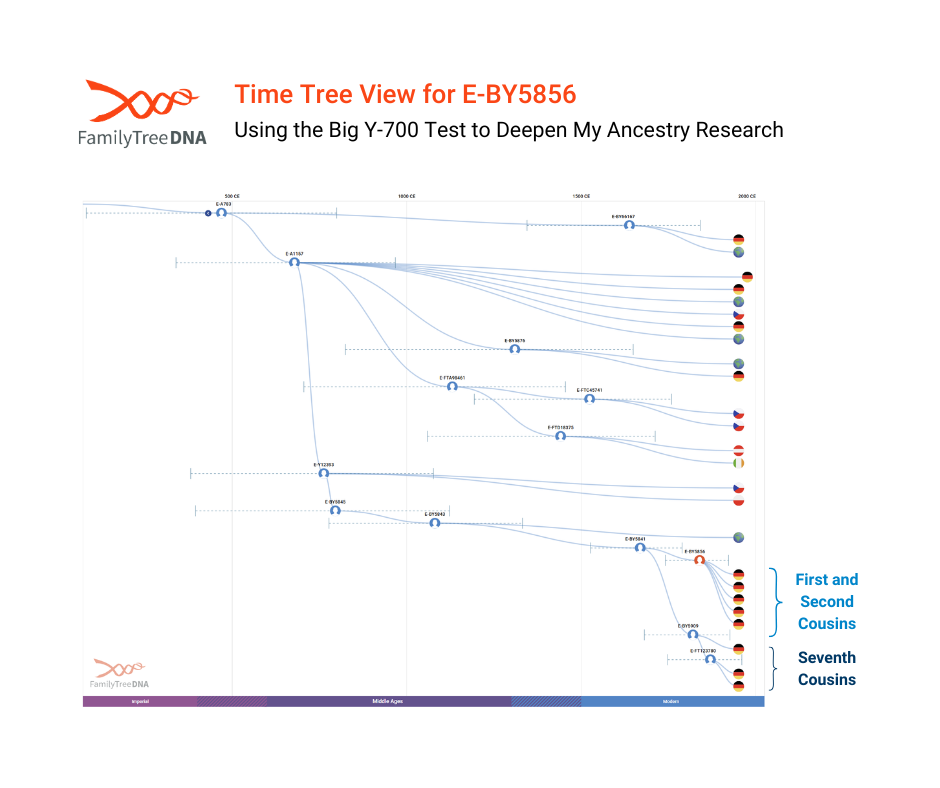

Visualizing Generations with the Time Tree

The Time Tree in FamilyTreeDNA’s Discover tools graphically illustrates how newly discovered Y-DNA mutations branch over time.

What it shows:

-

-

- How my family’s line diverged from related branches based on Big Y-700 SNP data

- The estimated generation or ancestor tied to each mutation

- Connections to other testers whose Y-DNA matches share parts of my lineage

-

By comparing data from my first, second, and seventh paternal cousins, I could see where our family split into distinct branches.

We can bring this long progress from ancient history back into the modern era of family research using these new Discover tools. Depending on data generated by other related Big Y testers, I can even assign a name or generation to the ancestor who first acquired each new mutation.

There is also the Match Time Tree, which creates a purely genetic family tree—built from shared Y-DNA rather than paper records—offering a powerful way to confirm relationships among men who share a common paternal ancestor.

Bringing the Story Full Circle

Working back to when and from where my ancestors arrived in the town of Moosbach, in Bavaria near the Czech border, may be impossible. I can even be accused of confirmation bias as I look at the evidence collected. But it appears to me that my ancient ancestors traveled out of Africa, through the Middle East, Anatolia, the Balkans, and Eastern Europe before finally settling in Bavaria.

This hypothesis provides a sense of satisfaction, family lore, and homecoming on my journey to becoming German.

With this reassurance of my German heritage and ancestral right to wear my lederhosen, I wish you all “Erfolgreiche Ahnenforschung und ein Schönes Oktoberfest!”

About the Author

Andrew Hochreiter

Group Project Administrator

Andrew Hochreiter is a genetic genealogist who manages multiple DNA surname projects and has successfully applied DNA to trace several related family branches overseas. He has over 30 years of experience in genealogical research with 17 years involved in genetic genealogy.

Andrew instructs continuing education courses in basic and advanced genetic genealogy at Howard Community College in Columbia, MD, and leads a Beginning DNA focus group at the Washington DC Family History Center. Previously, he was a facilitator for the genetic genealogy module of the on-line Genealogical Research Course at Boston University. Andrew writes a DNA column for the quarterly journal of the Mid-Atlantic Germanic Society and was featured on two Bavarian TV programs for his genealogical work tracing relatives in Germany using DNA. He serves as a director on the non-profit Accreditation Board for Investigative Genetic Genealogy.

Andrew is a great enthusiast and user of genetic genealogy as another valuable means to trace family history.