By: Roberta Estes

French surnames and “dit” names carry history, culture, and hidden clues that can help you trace your French and Acadian genealogy.

French names, like other names, were not spelled uniformly in the past, whether you’re talking about in France, in French-speaking colonies, or elsewhere in the world.

Our best source of early French records are Catholic parish registers, where births, deaths, burials, and marriages are recorded – sometimes with, and sometimes without parents’ names and locations if they were born elsewhere. Parish records also give us the ability to reconstruct families.

French names often consist of:

- First or “Saint Names”: Often a first name was chosen based on the calendar of saints. Common examples include:

- Jacques

- Jean

- Marie

- Jeanne

- Middle Name or Names: Children frequently received multiple given names, which could include those of parents, godparents, or other relatives, and baptismal names.

- Hyphenated Names: Hyphenated first names, like Jean-Baptiste, or Marie-Claire.

- Last Name or Surname: Originally used to distinguish two people with the same first, middle or baptismal names. Although not initially, french surnames today are typically passed down primarily through patrilineal transmission (from the father’s side)

- A “Dit” Name: A secondary surname or family nickname used to distinguish between two families with the same surname.

Names, and successions of names taken together, developed so that we could tell people apart, and we would know when someone was talking to us instead of 10 other people named Marie or John.

How French First Names Reflected Faith and Tradition

Many female babies were given the most common French name, Marie, or Maria if recorded in Latin. The Catholic church encouraged and sometimes insisted that a child be given a saint’s name for protection. Jehan is the Medieval spelling of the most common French boy’s name, Jean, or John in English.

Why Middle and Hyphenated Names Matter in French Genealogy

Saints names, or first names, were sometimes followed by either a middle or hyphenated name. Generally, these were the names by which the children were called on a daily basis.

For example, we could have:

- Marie-Anne or Marie Anne

- Jean Baptiste or Jean-Baptiste.

There is a distinction though, between the two.

Marie-Anne is a devotional name honoring two saints, Marie (the Mother Mary) and Anne (Mary’s mother), when hyphenated, and would generally be used as one name, with both words said together, but not always. This person could also have just been called Anne.

Generally, when we see a compound or hyphenated first name, there is no middle name.

If the name is written as Marie Anne, the name still honors two saints, but the name Anne would be considered the middle name, and the child would probably be called Anne within the family.

There are no hard and fast rules, though, and we often see information that can be confusing.

Case Study: Two Daughters Named Jeanne in Acadia

For example, Acadian parents Jacques Bourgeois and Jeanne Trahan named their daughter, born about 1644, Jeanne. They also named their youngest daughter Jeanne, who was born about 1667.

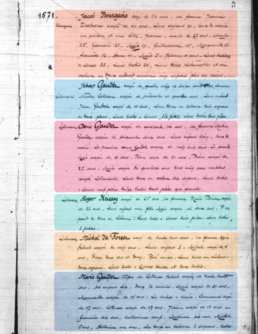

Both of these children, by that name, are reflected in the 1671 census. It’s likely that both children had a middle name too, but not all records reflect middle names.

1671 census image from the Acadians Project on WikiTree

The Origins and Meanings of French Surnames

Surnames, or secondary names, originated or evolved to distinguish two people with the same first, or baptismal, name, or families, apart from each other. They weren’t typically inherited at first. They described traits, jobs, or places.

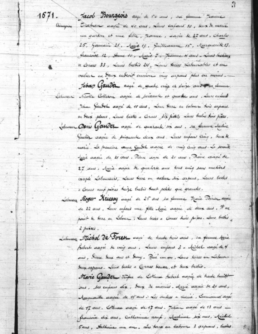

Surnames developed locally, so the younger man of two named John, “John the younger” might be named Jehan or Jean Le Jeune in his French village, while his brother might be named Claude Petit, because he was small, or smaller than the other Claudes in the village. Their father, also named John might be called, Jehan L’Aîné, or John the elder.

Initially, surnames were not heritable, so they did not descend to children and were not (necessarily) inherited from parents.

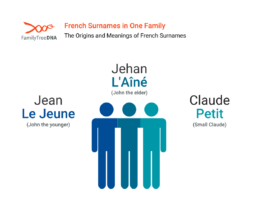

Needless to say, people changed their last names from time to time. When John Le Jeune was no longer the young John, maybe he became Jehan L’Aîné, or even Jehan Le Blanc, “the white,” describing his hair and beard. Maybe John moved to the next village and became John of the [old village name].

Secondary names, that eventually became surnames could reflect something about the person, a personality trait, where they lived, an occupation, or something else.

From Briard to Dufour: What Surnames Reveal About Ancestors

Each surname is a breadcrumb. You can often trace where your family lived, what they did, or even how they looked. For example, the surname Briard might suggest a family origin in the French region of Brie, as would de Briard, with “de” signifying “of” or “from.” Of course, they would probably only be known as Briard after they had moved someplace else.

The surname of Dufour means, literally, “of the oven,” so rest assured that someone in this paternal line was a baker – and probably one of a long series of bakers in a particular village. After all, a baker was a time-honored, well-respected craftsman, and who didn’t eat bread? Fresh bread was baked every morning and still is in France.

Le Boucher was the local butcher, and de la Forêt indicated someone who lived in or near the forest.

Hints held within the surname itself include prefixes such as:

- “De” or “du” meaning “of” or “from”

- “Le” or “La” meaning “the”

Someone with the surname of d’Aulnay, could be from the region of Aulnay, or at least where that region was when the name was adopted or conferred.

The prefixes “de”, “du”, “le”, or “la”, when followed by a word beginning with a vowel is joined with an apostrophe.

These prefixes are essential for context.

Over time, some names morphed into something else. For example, is the surname Dugas, also spelled Dugast and similarly in Acadia (now Nova Scotia) in the 1600s, spelled the same way in France? Could it have at one time been “De Gas” or “Du Gas” or something else?

We don’t know, but there has been a lot of speculation about that topic. We won’t know until confirming records are discovered in France, or Y-DNA testing confirms a connection to a French family. That hasn’t happened – yet.

How French Surnames Evolved from Nicknames to Law

Of course, surnames, first adopted by the upper class, evolved from their earliest uses. As villages grew, surnames began being adopted by craftsmen, then spread through the peasant class.

In the 1300s, the use of surnames was fairly widespread, and by 1474, King Louis XI of France issued a decree requiring that he approve all changes to surnames.

Surnames weren’t uniformly recorded in parish baptismal records. After all, everyone in the village knew who had a baby.

In 1539, King Francois I and the Parlement of Paris enacted the Ordinance of Villers-Cotterêts, which, among other things, required Catholic priests to record the child’s surname and register the birth. If your ancestor’s surname suddenly appears after 1539, that’s why.

Tracing French Surnames in Parish Registers and Records

However, some surnames were not recorded with the baby’s baptismal name, but in the margin, and surnames were spelled however the priest recorded them, leading to many variants of the name. Regional language differences varied widely. A name in one record that reflected a trade could be a completely different word in another region.

At that time, babies were given the surname of the father, unless the father’s name was unknown, then the child was baptized using the mother’s surname.

One of the very best things about French records is that females did NOT take the surname of their husbands when they married.

Baptismal, marriage, and other records are always found with both parents listed with their birth surnames.

Death and burial records of women reflect their birth surname as well, although they do sometimes say that they are the wife, or widow, of a specific man, or men.

During the French Revolution in 1789, some families changed their names for safety, and the requirement to register births was extended to people of all faiths, meaning not just Catholics.

In 1808 and 1811, Napoleon mandated the adoption and civil registration of all surnames for all his subjects, if families didn’t already have one.

Still surnames remained fluid.

Royalty, Titles, and Multiple French Surnames

Some people were known by multiple names.

Take King Louis XVI, for example. King Louis XVI was known by that name, but his father was Louis-Ferdinand (surname) Bourbon, Dauphin of France. Louis’s patrilineal surname would have been Bourbon.

After King Louis XVI was deposed in 1792 during an uprising, he was stripped of all of his titles and was known simply as “Citoyen”, citizen, Louis Capet, reducing him symbolically to a simple citizen before his trial, and eventual execution.

The surname Capet harkened back to Louis’s ancestor, Hugh Capet (941-996), who founded the Capetian dynasty, including the Bourbon line of French kings.

This dynasty was known as the “House of France,” so sometimes Louis was also known as Louis de France. Four names, same man.

Of course most of us aren’t descended from royalty or even minor nobility, so we need to search for our ancestors’ records.

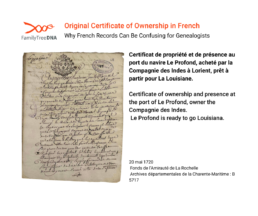

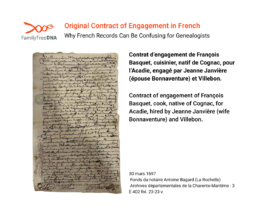

Why French Records Can Be Confusing for Genealogists

Original records are sometimes difficult to decipher due to record degradation and archaic handwriting, combined with either Latin or period-specific language.

In some locations, wars, fires, and other factors have resulted in the loss of all records. In others, the records still exist, but have not been transcribed and indexed, or made widely available.

And then, of course, for those whose families moved away, we don’t know where to look back to.

Which brings us to the topic of surnames and colonization.

Acadian Surnames and the First French Families in Nova Scotia

The first French families began to settle Acadia, today’s Nova Scotia, in the 1630s. No parish records exist in Port Royal, the Acadian capital, until 1702, but the first Acadian census was taken in 1671.

Satellite colonies began to be established around 1672, and 11 more censuses were taken between 1671 and 1714, although some censuses were only regional and didn’t include everyone, or the records no longer exist.

While there is a significant gap of nearly forty years between the arrival of the first families and the first census, census records help us immensely to reconstruct families. Fortunately, women are recorded using their birth surnames.

This census page shows information for several families including:

- the father’s occupation

- the names and ages of each family member

- the number and type of livestock owned by the family

- how many arpents of land, similar to acres, are under cultivation.

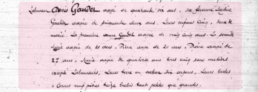

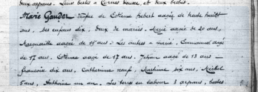

You can see how names could easily be mistranscribed. For example, is the name of the third family Gaudis?

Nope, it’s Gaudet.

How about Michd or Michel de Foren maybe?

Nope it’s Michel de Forest or de Foret.

Next is Marie Gander?

Nope, Marie Gaudet.

Census takers haven’t changed much – and this census was taken by the local priest. Even though the parish records from this era no longer exist, they would have been penned by the same hand.

As the priest changed, so did the writing, and the spellings, in the parish registers.

And just when you think you’ve got this, there’s more. Kind of like a bad Dad joke.

Surnames have nicknames, too.

What Are French “Dit” Names and Why Do They Matter?

Dit names are found associated with French families in Acadia, Canada, and somewhat in France. They are important because the person, and his family members, may be called by their surname, by their dit name, or some combination of both.

What is a “dit” name?

Dit literally translates as “said” or “called.” Dit names are essentially nicknames. They may be based on a location where someone came from, something about them, or something else.

Before the French Revolution, French soldiers were generally required to have a “dit” name, known as a “nom de guerre,” or war name. Military records used those names, and in essence, that name became your military identity.

I can only imagine how those names were acquired. In some cases, that name became their surname, and sometimes their only name, after their service.

Anytime I see someone called by only their dit name, I always consider that they may have been a soldier. Many Acadians arrived as soldiers.

To make things even more interesting, sometimes the person is only called by his dit name, not even his first name – during their lifetime, and even after their death.

Julien Lor dit La Montagne: One Man, Many Names

My ancestor’s name is Julien Lord, or Lore, or Laure, or Laird, or L’or, or Lort, or Laur, or dit La Montagne. What?

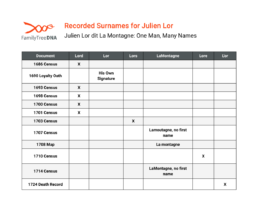

Julien is not recorded in the 1671 census, but his name in subsequent records varied as shown below.

Julien’s children and grandchildren’s birth, marriage, death and other records reveal further variations of his surname.

One of the challenges with dit names is that if you’re looking for someone by their surname, and you don’t know the dit name, you’ll miss them entirely.

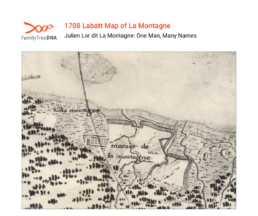

We are fortunate that there are two contemporaneous maps that show us the area where Julien lived, but they are both recorded as “La Montagne.” The first, drawn in 1708, shows both his house along the banks of the river, and his marais, or “swamp,” which means reclaimed saltwater marsh being farmed.

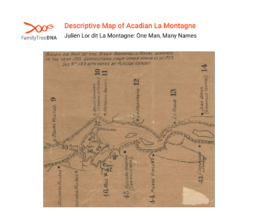

A map based on a 1733 survey, 9 years after Julien’s death, still reflected the location where his family lived, and probably still lived in 1733, as “La Montagne.” That’s clearly how the family was known.

Were it not for the combined census records that list his wife with her surname, and his children by their ages, we would have no way of knowing that he was recorded by various forms of Lore/Lore (and so forth), AND La Montagne.

Julien’s wife’s burial record in 1742 records her name as Anne Girouard, widow of Julien Lor dit La Montagne.

Juliens’ children used the various surnames and different spellings, including LaMontagne, although that seems to have faded into oblivion within a generation or so.

Is there a clue in all of this as to Julien’s history? Probably, but we have yet to decipher its meaning.

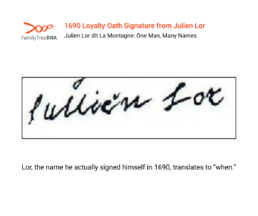

Lor, the name he actually signed himself in 1690, translates to “when,” but L’or translates to “gold,” and La Montagne translates to “the mountain.”

Julien was believed to be a soldier who came to serve, married, and stayed. However, he also lived between the river and the mountain. Maybe Lor had a specific meaning in France, and he became known as dit Montagne in Acadia.

How Land and Titles Shaped French Surnames

While La Montagne became a nickname for the entire family of Julien Lord/Lore (and other spellings), that’s not always the case.

Another Acadian, Philippe Mius, was born about 1609, probably someplace in Normandy, arrived in Acadia in 1651 as the adjutant to Governor Charles de La Tour, and became the King’s Attorney in 1670.

In 1653, he was granted land as “Philippe Mius, Esquire, sieur d’Entremont.”

This extensive land grant, “one leagues in width and four in depth in the place called Pobomcoup to be enjoyed by the said grantees and successors with the title of baron”, constituted a barony, so he was then also known as Philippe Mius, Sieur d’Entremont, Baron of Pobomcoup.

The title “Sieur,” in conjunction with the land grant, indicates that Philippe, as the Seigneur, has the right and responsibility to manage and oversee the development of the seigneury.

The additional language that the grant constitutes a barony gives Philippe yet another title that he could use.

In the 1671 census, he is recorded as “Philippe Mius, squire, Sieur de Landremont”, in 1678 as Philippe Myus, and in the 1686 census, as “Le Sr. Dantrexmon Philipe Mius.”

Philippe’s children who lived to adulthood used different surnames.

Marguerite Mius and the Laverdure Line

Daughter Marguerite (c1650-1713) married Pierre Melanson/Melancon dit Laverdure (the greenery). In the 1686 census, she is called “Marie Mius Dautremon,”

Jacques Mius and the d’Entremont Family Legacy

Son Jacques Mius (c1654-c1735) is recorded in the 1678 census as Jacques Myus and he signs his name on a deposition as such in 1684.

In 1686, after inheriting his father’s seigneury, he’s recorded as Jacques Mius Sr. de Pobomcou, and in 1693, only as Sr. Bouboncou.

His eldest son and one daughter used the surname Mius, and the other 7 used the surname Mius d’Entremont.

For the most part, his descendants use the surname d’Entremont, many still residing in or near Pubnico, Nova Scotia, once the seigneury of Pobomcoup.

Abraham Mius de Pleinmarais: A Surname Rooted in Land

Son Abraham Mius de Pleinmarais or Premarais (c1658-1700) is recorded in the 1686 census as Abraham Mius, dit Plemarch, and in 1693, he is living beside his brother, “Sr. Bouboncoup,” and is listed as “Sr. Plemarais”.

He is listed by that same name in 1703, and his wife is listed as “Madeleine Plemaris” in 1707.

His land on the 1708 map is listed only as “Premarais.”

Pre marais translates to “meadow marsh.” Abraham’s dit name was clearly based on his landholding. His children used the surname “Mius.”

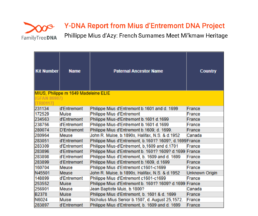

Phillippe Mius d’Azy: French Surnames Meet Mi’kmaw Heritage

Son Philippe Mius d’Azy, known as “d’Azy” took another path in life, married two Mi’kmaw women, and lived among the tribe. Philippe’s eldest son was listed in various locations as Joseph “d’Azy” including his 1729 death and burial record where he is listed as “Joseph MIeux dit D’azy”.

Philippe’s other children used the surname Mius, with the exception of two sons who used d’Entremont, but today, his descendants use the surname Mius.

As with other French surnames, Mius is spelled variously as well, including Muis, Meuse, and various forms of d’Entremont.

Viewing the Mius-d’Entremont DNA Project, we see that several of Philippe’s direct line male descendants have tested and matched each other. (Note: the Abraham Mius Pleinmarais/Premarais has no known direct male line descendants.)

If we didn’t know that men with the surnames of d’Entremont and Mius (and derivative spellings) were actually descendants of the same man, DNA testing would provide that information. If we had suspicions but weren’t sure, Y-DNA testing of men through multiple descendants would confirm it or dispel the myth.

The Expulsion of the Acadians and Lost French Surnames

Acadian genealogy is often difficult due to the 1755 expulsion, with the goal of severing all cultural and geographic ties to Acadia.

In 1755, the Acadians were rounded up and forcibly removed by the British in an event known as “Le Grand Dérangement.” They were herded onto separate ships, exiled from their homeland in Acadia, and scattered, primarily among the American colonies.

This displacement led to the Anglicization and frequent misspelling of their French surnames.

A few Acadians were able to return to Acadia a decade or so later, but to different locations, as their land had been given to English settlers. Some left the colonies and regrouped in Quebec.

Eventually, many Acadians made their way to Louisiana and became the Louisiana Acadians, or Cajuns, becoming part of a larger melting pot.

Many simply vanished into the colonies, their identities obscured over generations. DNA testing of descendants is the only way to bridge that gap, reconnect the dots and restore their rightful Acadian heritage. DNA testing is often the only way to make that connection when no records exist.

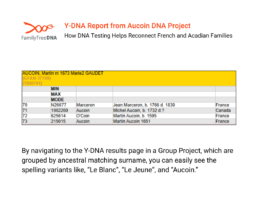

How DNA Testing Helps Reconnect French and Acadian Families

In addition to joining relevant surname projects, people of French descent often join the French Heritage DNA Project, and Acadians also join the Acadian Amerindian DNA Project at FamilyTreeDNA.

Males with French surnames take the Y-DNA test to trace their ancestors and match others by the same or different surnames.

By navigating to the Y-DNA results page for these projects, which are grouped by ancestral matching surname, you can easily see the spelling variants. For example:

- Le Blanc (white) has become “White“

- Le Jeune (young) has become “Young“

- Aucoin has become “O’Coin“

Just by browsing, you can discover possible origins and permutations of French surnames.

For example, we find a Marceron DNA match to the known descendants of Martin Aucoin and Michel Aucoin. Their ancestor Jean Marceron was born in 1766 and died in 1839.

A little genealogical sleuthing reveals potential birth and death records, in France, listing Jean Marceron’s parents as well. An Aucoin match to a Marceron is an EXTREMELY IMPORTANT clue, revealed by DNA testing.

We don’t know if Marceron is a derivative of Aucoin, vice versa, or neither. Chicken or egg. The surnames sound similar. This lead holds the potential to break through genealogical brick walls and could not have been discovered without DNA testing.

Y-DNA testing is the only way to know for sure which surnames you match. Only males can take the Y-DNA test, which tests the direct surname line, only, providing comparison and matching tools to other testers.

While women don’t have a Y chromosome to test, they can recruit fathers, brothers, uncles, or others who descend appropriately from surname lines they want to test.

The adage of, “you don’t know what you don’t know,” is especially true with French surnames and DNA testing. Aside from the normal confusion rooted in how surnames were adopted in the first place, French descendants have complications like dit names, multiple spellings, and anglicization of the surname.

Y-DNA, mtDNA, or Family Finder: Which Test Uncovers Your French Roots?

Both men and women, with direct matrilineal French ancestors (meaning from their mother’s mother’s mother’s line through all females to you) can take an mtDNA test.

Of course, autosomal DNA testing provides matches to cousins back five or six generations, and sometimes further.

There’s a saying in Acadian genealogy circles, “If you’re related to one Acadian, you’re related to all Acadians.” For the 120 years or so that Acadians lived in Acadia before being scattered to the winds, they intermarried within a relatively small population of several hundred people.

Find Out If You Have Acadian Ancestry Through DNA

If you’re a male, does your Y-DNA descend from an Acadian man?

Does your mother’s direct line matrilineal DNA descend from an Acadian woman?

Who are you related to? Test and see what secrets are just waiting to be revealed!

About the Author

Roberta Estes

Genealogy Subject Matter Expert

Roberta Estes, author of the book, DNA for Native American Genealogy, The Complete Guide to FamilyTreeDNA, and the popular genetic genealogy blog DNAeXplained is also a scientist, National Geographic Genographic affiliate researcher, Million Mito team member, and founding pioneer in the genetic genealogy field.

An avid 40-year genealogist, Roberta has written over 1600 articles at DNAeXplained about genetic genealogy as well as how to combine traditional genealogy with DNA to solve those stubborn ancestor puzzles. Roberta took her first DNA test in 1999 and hasn’t stopped.