Genes and Screams is a seasonal series linking genetic genealogy with history’s spookiest figures. Discover how DNA sheds light on mummies, vampires, and witches across time. You can read the rest of the series here:

By: Courtney Eberhard

From New England’s vampire graves to Transylvania’s royal bloodlines, DNA sheds light on the real origins of vampire legends.

If you joined us for our last Genes & Screams adventure, you know we started by unwrapping the mysteries of mummies. But while mummification preserved the body, vampire legends were born from what happened after the body was buried.

In pop culture, vampires sparkle, snark, and occasionally sign record deals. They fall in love (Twilight), feud with werewolves (The Vampire Diaries), navigate eternal high school angst (First Kill), wrestle with morality (Sinners), and host awkward dinner parties (What We Do in the Shadows). But before they hit streaming services, vampires haunted graveyards and village lore.

These were not creatures of romance — they were warnings. Long before we blamed glitter or garlic, real people feared that disease, decay, and death could rise again. And somewhere in those fears lies the first spark of the vampire myth.

That’s where DNA comes in.

By studying the remains once mistaken for monsters, genetic research reveals the very human origins of the undead. Because when science looks beneath the folklore, even legends have lineage.

Where Do Vampire Legends Come From?

Long before Bram Stoker’s Dracula took shape in print, villagers across 18th-century southeastern Europe whispered about the undead. The word “vampire” entered Western record when folklorists began documenting these oral traditions — tales of revenants, witches, and restless spirits blamed for unexplained deaths. In some communities, fear spread so quickly that it led to mass hysteria and even public exhumations of suspected vampires.

According to folklorist Paul Barber, author of Vampires, Burial, and Death: Folklore and Reality, such legends were early attempts to explain the natural process of decomposition. When graves were reopened, bodies sometimes appeared “well-fed” and ruddy, with dark fluids seeping from the mouth or nose. In reality, these were byproducts of decay — gases swelling the torso and forcing blood outward. Even the eerie groans heard during staking could be explained by escaping gases moving past the vocal cords. To pre-industrial villagers, though, these sounds and sights meant only one thing: the dead were alive again.

These fears weren’t limited to the Balkans. Archaeologists have uncovered “anti-vampire” burials across Europe, including in Britain and Ireland, where bodies were pinned down or had stones placed in their mouths to prevent them from rising. Bioarchaeological research by Paul Sledzik and Nicholas Bellantoni found similar practices in 19th-century New England, where outbreaks of tuberculosis were blamed on the dead “feeding” upon their relatives. DNA evidence from some of these graves now connects the supposed “vampires” to ordinary families devastated by epidemic disease.

Later medical theories tried to explain other elements of the legend. In 1985, biochemist David Dolphin proposed a connection between vampirism and the rare blood disorder porphyria — a theory popularized in the media but dismissed by medical experts for misunderstanding both the disease and the folklore. Neurologist Juan Gómez-Alonso, writing in the journal Neurology, suggested a far more plausible link to rabies: a disease spread by bites that causes sensitivity to light, disturbed sleep, and violent outbursts. The association with wolves and bats (both carriers of rabies) may have reinforced the connection.

Ultimately, vampire legends thrived because they gave shape to fear. They offered a way to explain the inexplicable. The sudden spread of illness, the mystery of decay, and the ache of grief. In every version, from the Balkans to New England, the vampire reflected humanity’s struggle to understand death itself.

And though modern genetics can’t resurrect those beliefs, it can trace their roots, revealing that the first “vampires” were victims of disease, not demons of the night.

Are Vampires Real? What DNA Can—and Can’t—Tell Us

No immortal blood-drinkers have ever walked among us, but the people accused of being vampires were entirely real. Their bones rest in churchyards and family plots across Europe and North America, marked not by fangs or capes, but by fear.

Archaeologists and bioarchaeologists have uncovered dozens of so-called “vampire burials” or graves altered in ways meant to restrain the dead. In some, stones were forced into mouths or iron stakes pinned the limbs. In others, bodies were buried facedown or decapitated to prevent them from “rising.” These practices, once driven by superstition, now serve as data for scientists studying how communities responded to epidemic disease and social panic.

Through Y-DNA and mtDNA analysis, researchers have traced many of these remains to ordinary families who lived during outbreaks of plague or tuberculosis. Genetic links connect them not to monsters, but to neighbors, parents, and children who shared the same DNA as those who feared them. The evidence transforms the story of the vampire from myth to microbiology — a window into how illness, isolation, and grief spread through generations.

And yet, legend endures. Each excavation, each genetic sequence, reminds us that behind every tale of the undead lies a deeply human truth: our ancestors didn’t fear the supernatural, they feared losing one another.

To understand why those stories still haunt us, scientists turned to the evidence left behind — bone, blood, and DNA.

What Have DNA Tests Revealed About Vampires?

While myths thrive on mystery, science thrives on evidence. Through DNA analysis, researchers can trace the remains once labeled “vampires” back to real families and living descendants. These genetic connections reveal that the so-called undead were not creatures of the night at all—but ordinary people caught in moments of fear, disease, and history.

The Griswold “Vampire” — Haplogroups R-FTG54720 (Y-DNA) & K1a3a1b (mtDNA): The Farmer Who Wouldn’t Rest

In 1990, boys playing near a sand and gravel pit in Griswold, Connecticut, uncovered an old family burying ground. One grave stood apart. Brass tacks on the coffin lid spelled “JB 55,” and inside, the skull had been severed and placed over crossed femurs. The classic skull-and-crossbones arrangement associated with New England’s 19th-century “therapeutic exhumations” during tuberculosis panics. Bioarchaeology noted rib lesions typical of chronic pulmonary infection, consistent with tuberculosis/consumption.

With modern tools, a research team revisited the case. Y-STR profiling and Y-SNP testing placed JB 55 within haplogroup R1b, a branch of R-P312 common in Western Europe. Later analysis shows his Y-DNA haplogroup as R-FTG54720. His mtDNA belongs to haplogroup K1a3a1b. Using the FamilyTreeDNA R1b Project, researchers compared his profile against living testers in the same subclade and found two near-identical Y-STR matches—both with the surname Barber. Archival records then linked JB 55 to a local farmer named John Barber, whose 12-year-old son Nathan Barber (coffin marked “NB 13”) was buried nearby, confirming the genetic connection.

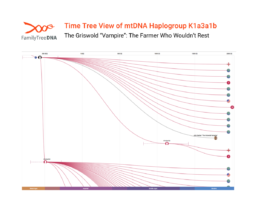

Facial approximation work by Parabon NanoLabs and the Armed Forces DNA Identification Laboratory, aided by VCU’s Virtual Curation Lab, later produced a digital reconstruction of Barber’s face.

So why was he treated as a “vampire”? In the early 1800s, tuberculosis epidemics devastated New England families. The disease’s symptoms included:

- pale skin

- sunken eyes

- blood at the mouth

These symptoms looked to grieving relatives like signs that the dead were feeding on the living. When more members of the Barber family fell ill, his relatives exhumed his coffin in desperation. Finding his heart already decomposed, they followed local ritual: breaking open the chest and arranging the bones in a skull-and-crossbones to keep him from “rising.”

The inscription “JB 55,” his initials and age, and the town where he was found gave rise to the name “the Griswold Vampire.” He remains the only archaeologically documented “vampire” burial in the United States. A man transformed by fear, folklore, and family into a legend that modern DNA finally returned to history.

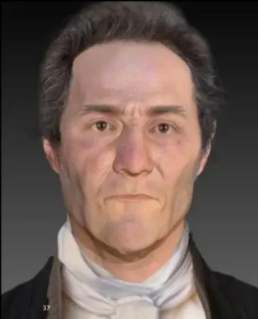

The Kilteasheen “Vampires” — Haplogroups R & I (Y-DNA): The Stones That Silenced the Dead

When archaeologists from IT Sligo and Saint Louis University excavated the medieval burial ground at Kilteasheen, County Roscommon between 2005 and 2009, they expected to find traces of a Gaelic royal settlement. What they unearthed instead was far stranger. Among more than 130 burials dating between the 7th and 14th centuries, two men stood out — each buried with a large stone forced into his mouth.

The men, one in his forties or fifties and the other a young adult, had been interred side by side and outside the cemetery’s consecrated ground. Their limbs were broken, their jaws nearly dislocated, and their bodies folded around boulders. Excavation director Chris Read, head of Applied Archaeology at IT Sligo, noted that such “deviant burials” were deliberate — evidence that the community feared these men might rise again.

Originally thought to be victims of the Black Death, radiocarbon dating revealed that these burials predated the plague by centuries, placing them between 600 and 800 CE. Instead of contagion, archaeologists believe these were revenant burials — early attempts to restrain the “walking dead.” According to Kristina Killgrove, a biological anthropologist at the University of North Carolina, in pre-Christian Irish belief, the mouth was seen as a portal for the soul, and sealing it with a stone may have been a way to prevent a restless spirit or malevolent force from returning.

While Ireland is better known for Gothic writers like Bram Stoker and Sheridan Le Fanu than for vampire folklore, Kilteasheen proves that tales of the undead existed here long before Dracula. These two men, now dubbed the “Kilteasheen Vampires,” may represent one of the earliest archaeological traces of such fear in Western Europe.

Ancient DNA analysis from the site shows typical Irish male lineages — primarily haplogroups R and I, both common in northwestern Europe. Within FamilyTreeDNA’s global database, individuals can now trace their direct paternal or maternal ancestry to burials from Kilteasheen. However, it’s unclear which of those ancient samples belong to the two “stone-mouth” burials. Once those correlations are confirmed, this record will be updated to reflect the exact haplogroups of Ireland’s earliest known “vampire” burials.

| Name | Y-DNA haplogroup | mtDNA haplogroup |

|---|---|---|

| Kilteasheen 2 | R-P312 | U1a1a3 |

| Kilteasheen 4 | R-BY21033 | U5a1f1a1 |

| Kilteasheen 7 | R-Z290 | T2b19b2 |

| Kilteasheen 9 | R-DF104 | K1a4a1af1 |

| Kilteasheen 14 | R-DF105 | J1c1a |

| Kilteasheen 15 | R-L21 | V10a |

| Kilteasheen 16 | R-FT353845 | J1c |

| Kilteasheen 18 | I-M423 | H1e1a43 |

| Kilteasheen 19 | R-M222 | K1c2+16311 |

| Kilteasheen 20 | R-Z2186 | V1a18 |

| Kilteasheen 22 | R-A22 | U4b1b2 |

| Kilteasheen 24 | R-P312 | J1c3f |

| Kilteasheen 25 | R-BY75760 | U5a1a |

| Kilteasheen 26 | R-DF13 | T2b^ |

| Kilteasheen 27 | R-FT155025 | H7a1b |

| Kilteasheen 30 | R-S841 | U5a1a1 |

| Kilteasheen 32 | R-FT371190 | U4a1a |

| Kilteasheen 33 | R-BY122668 | K1a4a1 |

| Kilteasheen 34 | R-BY42759 | H3ao |

| Kilteasheen 35 | R-FT371190 | H1b51 |

| Kilteasheen 37 | R-DF104 | H13a1a |

| Kilteasheen 38 | R-P310 | I4a |

| Kilteasheen 41 | R-DF105 | V3a1a"g |

| Kilteasheen 43 | R-DF13 | I2 |

| Kilteasheen 44 | R-DF105 | U5b2c2b |

| Kilteasheen 45 | R-P310 | U5a1g |

| Kilteasheen 47 | R-BY21033 | H32a^ |

Data from Gretzinger, J., Sayer, D., Justeau, P. et al. The Anglo-Saxon migration and the formation of the early English gene pool . Nature 610, 112–119 (2022).

Through DNA testing, modern descendants can see if their lineage traces to this medieval Gaelic burial ground — and perhaps to the very people once feared to rise again.

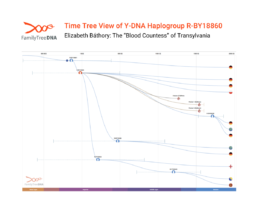

Elizabeth Báthory — Haplogroup R-BY18860 (Y-DNA, House of Báthory): The “Blood Countess” of Transylvania

In the shadowed hills of Transylvania, few names echo louder than Elizabeth Báthory. Known to history as the Blood Countess, she was accused of torturing and killing scores of young women and legends later claiming she bathed in their blood to preserve her youth. While such tales made her a staple of gothic folklore, the truth behind the myth is far more complex.

Born in 1560 into one of Hungary’s most powerful noble families, the House of Báthory, Elizabeth was educated, multilingual, and politically astute. But her life unfolded against a backdrop of turmoil: Protestant nobles like her family clashed with the Catholic Habsburg Empire, and power struggles within Transylvania made her immense wealth dangerous. When accusations arose that she had murdered hundreds of girls, the investigation was swift and severe. Her servants were tortured and executed, while Báthory herself—shielded by rank—was imprisoned within the walls of Čachtice Castle, where she died four years later.

Modern historians and medical scholars have since revisited the evidence. Many now view her story as one of Europe’s earliest politically motivated witch-hunts, inflated by fear and misogyny. The infamous “blood-bathing” legend appeared more than a century after her death, likely born from rumor rather than record. Yet, certain details—like reports of blood at her lips—may have stemmed from her real medical condition.

Contemporary accounts describe Báthory as suffering from epilepsy, known then as the “falling sickness.” At the time, treatments included placing a few drops of another person’s blood on the lips of the afflicted or having them ingest it after a seizure. This misunderstood ritual, coupled with the imagery of blood and fainting, could have easily evolved into the myth of a woman who fed on youth to sustain herself.

Unlike New England’s or Ireland’s “vampires,” Báthory was never exhumed or tested—but her family’s genetic legacy has been traced. A 2023 study identified the Y-DNA haplogroup R-BY18860 among confirmed male Báthory descendants, a lineage common among the Hungarian and Polish nobility.

Elizabeth Báthory may never have drawn blood from her victims, but history has feasted on her name for more than four hundred years.

Vlad III the Impaler — Haplogroup Unknown: The Prince Who Inspired the Undying

Known to history as Vlad Țepeș or Vlad Dracula, the 15th-century Voivode of Wallachia inspired centuries of fascination and fear. To Romanians, he was a national hero who resisted the Ottoman Empire. To Europe, he became the embodiment of cruelty — a ruler whose enemies were left impaled by the thousands. And to the world, his patronymic Dracula, meaning “son of the dragon,” would forever link him to fiction’s most famous vampire.

Vlad was the second legitimate son of Vlad II Dracul, a member of the Order of the Dragon, a chivalric brotherhood founded to defend Christendom from Ottoman invasion. Born around 1431 in Transylvania, he grew up amid political betrayal, captivity, and war. After reclaiming the Wallachian throne, he ruled through terror, executing nobles, impaling enemies, and imposing a brutal form of justice that his supporters later called necessary discipline.

Many of the grisly legends surrounding Vlad were born from German and Saxon pamphlets, among the first mass-printed “bestsellers” of Renaissance Europe. One infamous tale claimed he dipped his bread in the blood of his victims — imagery that would later echo through Bram Stoker’s Dracula. But modern historians agree: these accounts were wartime propaganda, exaggerated by rivals seeking to vilify a defiant ruler.

Yet the impalements themselves were real — and unforgettable. Vlad’s method of punishment involved driving long wooden stakes through his victims’ bodies and leaving them on display outside his capital at Târgoviște. The forest of skewered corpses horrified invading armies and cemented his reputation as a living nightmare. Centuries later, this macabre imagery likely helped shape the folklore of wooden stakes as tools to “kill the undead.” In myth, the stake shifted from an instrument of cruelty to a weapon of protection — proof that even horror can evolve from history.

Recent science has added a strange nuance to his legend. In 2023, researchers analyzing proteins and peptides from letters written by Vlad suggested he may have suffered from haemolacria, a rare condition that causes blood to mix with tears. If true, this natural disorder could explain historical reports of red-stained eyes and the “blood tears” described in contemporary chronicles. In other words — Vlad might not have drunk blood, but he may well have wept it.

Genetically, the House of Drăculești, a cadet branch of the Basarab dynasty, has not yet been fully sequenced. A 2012 population study targeting men of Basarab ancestry in Romania explored this connection but found no single defining haplogroup. Y-DNA haplogroups found among the Basarab sample population included E-V13, I2, and R1a, all common in southeastern Europe.

Vlad’s brutality was real, but his vampirism was literary. As Smithsonian historians note, Bram Stoker borrowed the name “Dracula,” not the man, crafting a fictional count whose immortality and appetite reflected Victorian anxieties more than medieval politics.

Vlad the Impaler may not have lived forever — but his legend has ensured that his blood, and his story, never truly died.

Why Do Vampire Myths Persist?

Even after centuries of science, the vampire refuses to die.

Psychologists and historians suggest that’s because vampire stories give form to what we fear most: death, disease, and the loss of control. They turn invisible threats into something we can name, confront, or even romanticize.

In early folklore, the vampire explained plague and premature burial. In the 19th century, writers like Ernest Jones, author of On the Nightmare, argued that vampires symbolized forbidden desire, guilt, and grief, the darker instincts we repress. And in modern times, the vampire has evolved again: no longer a symbol of decay, but of immortality, power, and escape.

The myth adapts because it mirrors us. When science ends one mystery, culture writes another. We may no longer believe the dead rise to drink our blood, but we still crave stories that let us face what haunts us — love, loss, and the inevitable pull of time.

What Can DNA—and Science—Reveal About Ancient Vampire Myths?

Garlic, silver, and wooden stakes didn’t appear out of nowhere. Long before film studios added fangs and fog machines, these symbols of protection were rooted in real attempts to stop disease and decay. Each one carries a trace of truth and a little human desperation.

Garlic: The Science Behind the Smell

Garlic’s reputation as a vampire deterrent may have deeper roots than superstition — and, surprisingly, a touch of science. In medieval Europe, garlic was thought to cleanse the blood and ward off plague. When sickness spread through villages, people hung bulbs in doorways, wore cloves around their necks, and rubbed it on the skin of the dead to “purify” them. Over time, that ritual defense became legend: garlic could repel not just disease, but the undead who carried it.

Modern studies have given the myth a tongue-in-cheek revival. A 2021 article in the Medical Journal of Australia explored whether garlic might actually deter “vampires” through measurable physiological effects. The authors proposed that garlic’s hypotensive properties (its ability to lower blood pressure) could make it harder for vampires to feed efficiently. They also noted that volatile compounds released from the skin and breath after eating garlic might form a natural “vampire repellent,” particularly around the neck, their favorite target.

While the study was written with humor, it reflects a truth at the core of folklore: ancient people observed real biological effects and spun them into meaning. Whether it’s lower blood pressure or pungent body odor, garlic’s protective power might not keep vampires away — but it certainly helped people feel like they had some control in the face of unseen dangers.

Silver: Purity, Protection, and the Science of Sacred Metals

The idea of silver as a weapon against vampires is actually a relatively modern addition to the lore, but its reputation for repelling evil goes back much further. Long before it appeared in vampire films, silver was used against all manner of haunted creatures: werewolves, witches, and restless spirits. In religious traditions from Europe to the Middle East, it symbolized purity and divine light — a metal too “holy” for the unclean to touch.

That symbolism wasn’t entirely unfounded. Centuries before germ theory, people noticed that silver vessels could keep water, wine, and even milk from spoiling. Its antimicrobial properties, confirmed by modern science, made it a natural emblem of health and holiness. When folklore blurred the line between infection and possession, silver became more than a precious metal — it was a shield.

In vampire stories, that purity translated perfectly: what could kill bacteria could just as easily drive out darkness. From the church altar to the monster hunter’s kit, silver’s role evolved from sacred to cinematic — a shining reminder of how human faith and early science often shared the same goal: protection from the unknown.

Your story may not include vampires — but it’s part of humanity’s shared history. Want to see if your line includes an accused vampire? Take a Y-DNA or mtDNA test and explore your results in our Discover haplogroup reports.

Frequently Asked Questions About Vampires and DNA

Q: Who were the first vampires in history?

The first written accounts of vampire-like beings come from 18th-century Southeastern Europe, but similar beliefs existed long before. Archaeological sites in Eastern Europe, Britain, and Ireland reveal “anti-vampire” burials — bodies pinned with stakes or stones to prevent them from rising. These individuals were often victims of plague or tuberculosis, not monsters. According to folklorist Paul Barber (Vampires, Burial, and Death, 1988), such legends began as attempts to explain decomposition in a pre-scientific world.

Q: Has a real vampire ever been found?

No evidence has ever confirmed the existence of supernatural vampires. However, archaeologists and geneticists have examined remains once believed to belong to them, like the Griswold Vampire of New England and the Kilteasheen burials of Ireland. DNA testing shows these “vampires” were ordinary people connected to families who lived through epidemics. The myth, not the body, is what endures.

Q: What does DNA reveal about vampires?

DNA can’t detect immortality or fangs, but it reveals ancestry, migration, and shared history. Through Y-DNA and mtDNA analysis, scientists have connected remains from “vampire” graves to living descendants. These tests show that many who inspired the legends were related to the very communities that feared them — proof that myths of the undead were, in truth, stories of survival.

Q: Why do vampires drink blood?

In folklore, drinking blood was never about romance — it was survival. Early communities saw blood as life itself, so legends of creatures consuming it mirrored fears of illness and decay. Psychologists like Ernest Jones (On the Nightmare, 1931) later interpreted the act as symbolic: a fusion of desire, guilt, and dependence. In biology, parasites and hematophagous animals survive the same way — by taking what their hosts can afford to lose. The myth endures because it captures the oldest human truth: life always feeds on life.

Q: Can DNA testing show if I’m related to these figures?

Yes. Y-DNA and mtDNA testing at FamilyTreeDNA can reveal whether your haplogroups connect to ancient or notable lineages studied by researchers. By comparing your results to our database, you can explore ancestral connections across centuries — including those linked to historical eras that inspired the vampire legends themselves.

About the Author

Courtney Eberhard

Senior Marketing Specialist

Courtney is driven by a profound passion for genealogy, fueled by her personal journey as an adoptee with roots in the LDS church. Through research with FamilyTreeDNA, she has also been able to uncover her son’s father’s indigenous roots in Mexico and provide context for his origins.

In her spare time, she finds joy in connecting with her family and friends during cookouts, cheering for the Houston Astros, and cherishing her role as a dedicated full-time parent.

I still look back with sentimentality towards Family a tree DNA…and my sadness when amU stopped running the Lees DNA site. But I became overwhelmingly disgusted with the idiots who refused to share whatever family data they have. Since then, I’ve joined most of the xompetitirs-veinh even more disgusted with ancestry’s idea of competition: just buy out all the other sites and close them down…except for relative genetics where they erased the paid customers and made everyone start over…and still, their customers mainly refuse to share family data. So I guess they’re happy to be told they are related to an apeman rather than a real man? Alas, Family Tree will always be the first/the foremost for me in DNA studies. Thanks for your wonderful efforts!

Sorry for mistakes. Since my stroke, I sometimes miss keys…

The Kilteasheen skeletons have been popping up in my DNA over 20+ of them and direct descendent of a few including the “vampires” the old beliefs before Christianity reached Ireland they believed in Samhain and believed that the dead came back which became eventually Halloween obviously it was a strong believed in holiday that remnants still in someways still celebrated. That being said me and my running of the mouth and colorful language I know looking out at my loved ones slain and knowing I’m next I’m telling them “you won’t stop me the gravy can’t hold me I’m coming for you” 😂 yeah I would be right there with them with a rock in my mouth and just to be sure they would have tied me to another rock. Say or do something outlandish to throw someone off guard sometimes that’s enough to turn the tides or get you tied to a rock. 😂☘️🇮🇪 Irish humor.

Are Vampires my real Family